ISW: I will not be able to ask you the first question that I should ask a Russian poet at this moment, because you live in a country where you might face severe consequences for answering it. We will have to conduct this conversation in the shadow of that fact as if it were something acceptable, which it isn’t. That means that my first question will have to be something else. So, I will start by giving you an opportunity to tell readers a little about your own background and experiences. What is it like being a contemporary Russian poet?

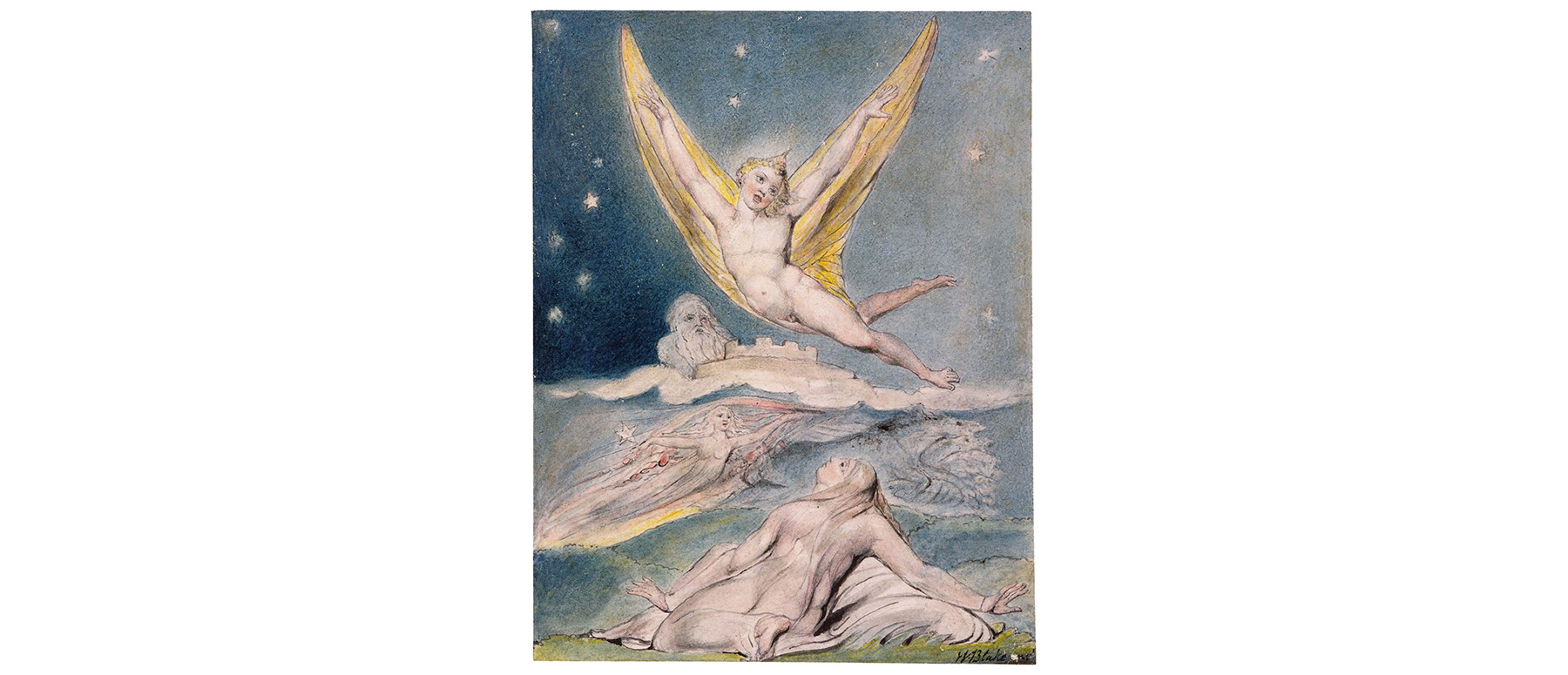

AP: I have always experienced the idea of a person’s “background” as a multifaceted one, and I am inclined to approach it first and foremost as a question about their cultural experience and inner reality, treating the elements of their biography as secondary. I have always been fascinated by the individual evolutionary paths of writers, but I have only found it useful as a lens through which I could view the work of others, so I find it hard to speak about myself in this register. After all, I experience my evolution as being far from complete; I deliberately cultivate the mentality of a neophyte and try to preserve a fresh eye on the world, its problems, language, and what poetry is capable of. I became a poet relatively late in life, and, as far as I can remember, I was always encountering difficulties that others did not seem to be experiencing, in the domains of emotional life, self-expression, and relationships with other people. I have had (and, alas, still have) health conditions that have baffled doctors. This has led to periods when I seemed to have limited points of genuine contact with reality, and my internal resources were also so meager that I sank into some dark shell hole of despair and disorientation. In my attempts to scramble out, I have grabbed hold of various domains of human knowledge and experience, whether it was philosophy, music, or art. In essence, before every poem I’ve written, I have found myself in one of those pits or at the bottom of a well, and my task was to grope for the tiniest handholds protruding from the wall and check whether or not the next handhold-word or rock-meaning could support my weight, the entire mass of my being. The experience of hauling myself out of a pit, expressed in words, is a poem. There were catalysts, of course. For example, when my son was born (I was 22), I felt that time itself spoke to me through the language of an event, and that event was a message addressed to me in a maximally personal way, like nothing else had ever been. My sense of self changed so much that there was no other conclusion; I had to truly come to understand my mode of existence, dismantle it down to the smallest component, pose the question of being in its absolute sense to my life—otherwise, what could I tell my son about life, about happiness and suffering, if I had failed to make sense of them myself? So I turned to poetry, first by translating it, and then as a way of groping for those points of interaction with life, time, and body.

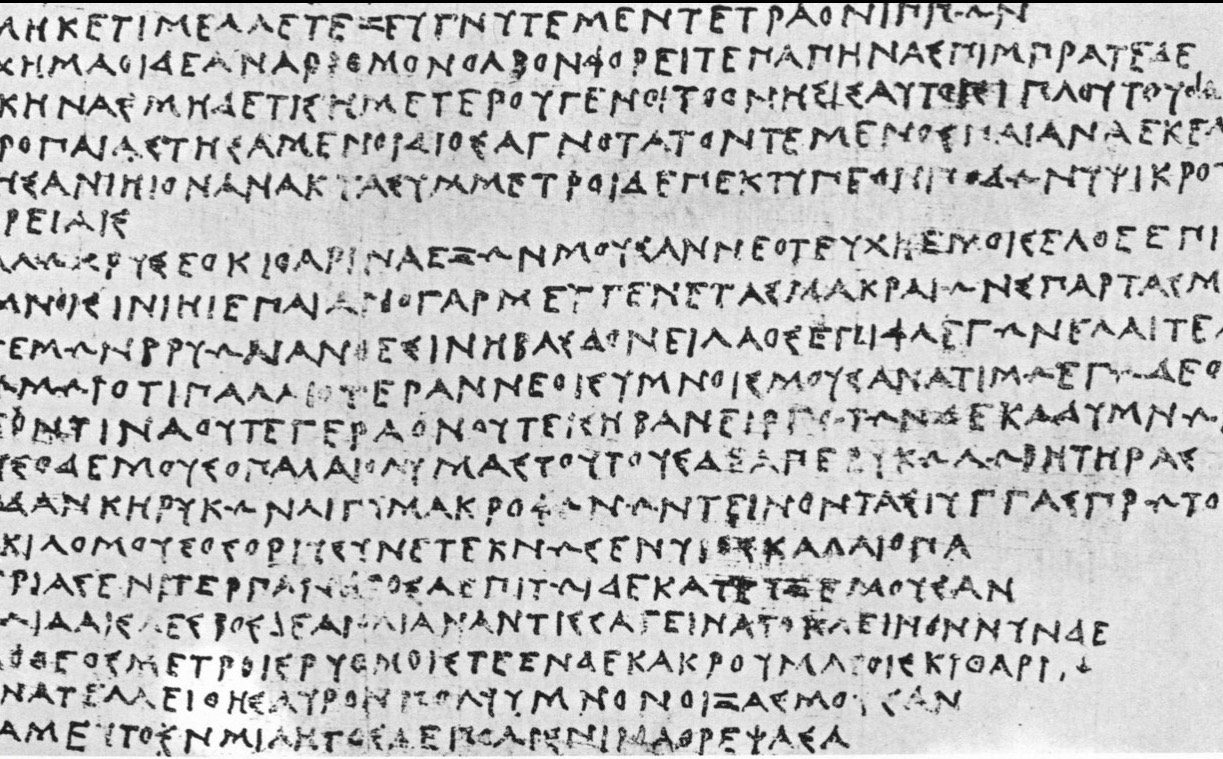

I think that being a contemporary Russian poet is just as complicated matter as being, for example, a contemporary Lithuanian or American poet. The problem lies in the very idea of the contemporary when it is understood in aesthetic terms. An artist does not have the option of adopting something directly from the past—that path is closed—but poetry as an art form, even as we remember it from the proto-poetic period of its development in the European context, requires a balance between “tradition” and “innovation,” which demands that the poet have a certain sensitivity to the artistic practices that may seem to belong to the past as well as those that are appearing in our own time. When it comes to recent political events and the associated widespread surge of Russophobia, being a contemporary Russian poet is more difficult; our entire culture and its achievements have been abruptly devalued in the eyes of contemporary society. For poetry, this means paying for our apoliticality and playing along with the fake reality created by our government. For Russian poetry, it also means the necessity of proving that we are not complicit with the violence, that we are actively opposing authoritarianism, and that we are dedicated to peaceful dialogue between peoples and the creation of a free society.

ISW: What should English-speakers know about the contemporary poetry scene in Russia? Are there are interesting developments you have observed lately?

AP: The poetry scene in Russia is very diverse. Indeed, we are currently witnessing a true flowering of poetry. One phenomenon that I can describe as relatively new for Russia is feminist poetry. There are strong conservative tendencies in Russian poetry, emphasizing the need to preserve the cultural baggage of bygone epochs—and their linguistic expression. In practice, this manifests as the view that rhyme and meter are essential, and one of the main arguments advanced by supporters of this position is the fact that Russian is an inflected language, and its wealth of grammatical endings leads to endless potential for rhyming versification. Free verse and irregular forms have also seen development through the work of many contemporary Russian poets. The landscape of contemporary Russian poetry really ought to be the subject of several articles, if not a huge body of them, but, to speak in general terms, one might point to tendency for groups of authors to be divided (it is never hostile or adversarial, however) along institutional lines, though authors can “migrate” between institutions or simultaneously belong to several of them. It would be pointless to list all of them, so I will simply point out the ones that are most significant from my point of view. For example, that includes the circle of authors around the literary magazine Vozdukh, published by poet, translator, and literary critic Dmitry Kuzmin, the poets around Translit, under the continuous editorship of poet and literary critic Pavel Arsenev—they conceive of poetry as closely related to political activism—the female authors around the F-letter project, who ground their aesthetic praxis in an exploration of the idea of feminism, the circle of authors around the New Literary Review publishing house, the authors participating in the Novaya Kamera Khraneniya project, created by Oleg Yuriev, Valeri Shubinsky, Dmitri Zaks, Olga Martynova, who are brought together by a certain intersection of their poetic techniques, which largely follow in the footsteps of the post-Acmeist tradition, etc. Simultaneously, the so-called “thick journals” have continued to exist. They are a curious phenomenon handed down to us from the Soviet period. Some of them are managing to overcome their ossified conservatism, but others have yet to change their editorial practices despite thirty years without the Soviet regime, and they are, in that sense, doomed. The political situation has split our society into two camps, and that same ideological opposition can be seen among poets and writers as well. I think that it is a line of demarcation, a pivot point in time. The future of Russian literature will develop in relation to this point, and, as the past teaches us, it is precisely humanistic appeals vested in the various literary genres that have a chance of becoming part of history. The supporters of violence have already lost, whether one takes a long-term or short-term view.

ISW: One of the interesting elements of literary life in Russia American translators often discuss is how unapologetically online it is. Why do you think the Internet plays such a significant role and what does that mean for poetry?

AP: I think the small number of journals, and publication opportunities in general, available to a contemporary Russian writer only partially explain that. Social networks truly are important to many people; by posting poems there, an author maintains a form of contact with the literary community, and experiences that community’s quick response to a newly written poem as a kind of support—“you exist,” “you are valuable,” “you are interesting.” The most important reason, however, lies in the general political atmosphere in the country, and in the Russian-speaking world generally; in the last few years, tinged by the collective awareness of the radical suppression of dissent, the opportunities for self-expression in the public sphere have grown more and more constricted, the remaining ones are censored, and speaking out directly at a demonstrated or during a protest action is widely understood as an impossibility, whether directly or indirectly, which means that social networks have become the place where it is possible to express yourself (though one must be wary of current laws—after all, people in our country have faced criminal and civil penalties for what they post or share on social media). Poetry is becoming part of online activism, as sad and pitiful as it may look. Due to the situation in Ukraine, the measures to suppress the protest movement have become harsher, which means all of these factors have been even more palpable.

ISW: One of the most challenging elements of translating your poetry into English for me has been that you are comfortable using abstractions that lack specific physical references. To put it simply, there are a lot more words ending in “ness” in your poems than in most contemporary American poetry. Could you say a few words about that aspect of your style?

AP: To one extent or another, I think that is inevitable for a contemporary poet; after all, our era is closely linked with contemporary philosophy, and all of those abstractions are becoming part of our consciousness, an inevitable element of our language. One can, of course, subordinate poetic language to some abstraction and engage in illustrating ready-made philosophical ideas, but, in my view, the time to reject the role of illustrator has long since come. Juxtaposing abstractions with physical objects gives me—and, I hope, the reader—the potential to defamiliarize them, see them from a new angle. It is an attempt to subordinate those abstractions to the laws of ordinary empirical perception. Poetry can be aligned to philosophy and other forms of knowledge, including non-scientific ones, but it can never occupy a subordinate position and be the handmaiden of any idea, mythology, or ideology, whether it be Marxism, feminism, or any other “ism” we might find useful. Including abstractions in a poetic text also has an open message; these abstractions are objects, just as palpable as a tree branch or a park bench, and my task in that domain is to show how human perception is refracted as it passes through a constellation of abstract concepts that are capable of organizing its existing experience and even constructing a new one.

ISW: One of the critical moments in your career was when you began to write political poetry. What brought about that decision?

AP: The impetus was the situation in Ukraine, the immense contradictions that began to intensify around 2014 and led to an armed conflict, the escalation of which we are witnessing today, along with the general political situation in Russia and the world. This is not only due to my personal circumstances (my family, on my father’s side, traces its origins to Ukraine), but also because, in general human terms, this was an ordeal for many people, and I experienced the need to respond to it almost instantly. This subject is new to me, and it has affected the form of my poems, made it freer. I felt with great clarity that it was impossible to write about war and violence using strict meter and rhyme; given the evocative quality characteristic of such forms of poetry, there would always be some scarcely perceptible element of the verse that would be rhapsodic about the source of violence, gazing it in with adoration, while the mission of poetry is universal peace and the remediation of violence. Universal peace and a life without violence is, of course, an ideal that many will view as unattainable, but that is what ideals are for, inspiring us to endlessly strive for them. We are currently paying for our years of apoliticality. The politicization of art is a necessary step on the path to genuine freedom for society and the individual.

ISW: I would like to follow up on the idea of the politicization of art. As a translator of literature from Ukraine and Russia, I have often noted that Americans tend to read work from the area for its political relevance, not its literary and aesthetic merits. Do you think that pattern is a concern, and how is it relevant to your experience?

AP: I am certainly concerned about that situation, when people begin to experience poetry without deploying the aesthetic frameworks of the other artforms—which is what enables us to understand poetry as “painting with words” or “the music of verse” or “the science of metaphor—” and instead simply check for the presence of political shibboleths. That tendency also exists in Russian literary criticism. Without impugning poets’ political agendas or how they manifest them in their work, I would prefer if people continued to view poetry as an artform, with an enormous range of associated aesthetic elements. The vocation of poetry is to transform consciousness, and poets must use the full arsenal of poetic techniques, developed over the course of centuries, constantly striving to expand it—after all, any political agenda and the associated language has already been formulated by someone else, and uncritically accepting these ready-made semantic assemblages would mean violence against one’s own consciousness and the consciousness of others, since a poet, in my view, can only accomplish his mission by grounding himself in extreme nonviolence.

ISW: How important is it to you that your poetry reach audiences in the English-speaking world?

AP: It is very important to me, and very valuable. I love the English language and its literature and culture. It is a joy for a poet to be heard and understood in different corners of the world, and I have been blessed with that experience, for which I am boundlessly grateful—especially these days, when everything Russian seems discredited. It is important to express the simple truth that the people and the government are not one and the same, and, indeed, the Russian people have found themselves in the position of hostages.

ISW: How do you expect Russian culture and, for lack of a better word, Russian consciousness, to change as a result of the terrible times we are living in?

AP: I expect the social schism we have already mentioned to intensify, and that will inevitably affect the creative sphere. A great deal will go into expiation of our guilt for what has happened to the innocent victims, into ridding ourselves of this shame, and into transforming that historically conditioned shame into political action that will help us to create civil society and the rule of law. A great deal will go into seeking out and manifesting the reality we have been forbidden to see for many years, forbidden to call things by their right names. A certain pathos of repentance is emerging in many literary genres, tinting the intonation of many current and recent authors. We may also see the emergence of militaristic literature, rhapsodizing about violence in the name of a just cause and glorifying the imperial spirit, and it is that aforementioned struggle between value systems that produces the electric potential difference required for fruitful cultural development. This may be my optimism talking, but I want to believe that even the most difficult times can lead to such flourishing. On the whole, there will be two competing images of Russia—that of a great empire, a nuclear power imposing its will on the world, and the image of a Russia where the primary values are the life, health, happiness, and wellbeing of every individual person. These two images, these two vectors of development, as we have observed in practice, are incompatible. We have a great deal of work ahead of us to bring our country back into the domain of civilized dialogue. We have a long road ahead before our homeland is restored to us.