“The universe is full of eyes.” —Robert Duncan

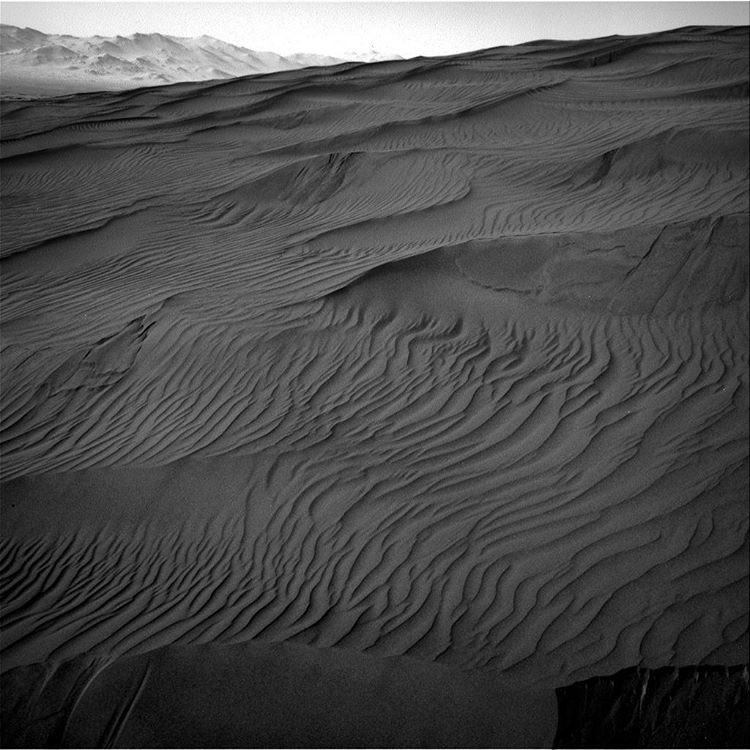

In summary, the slaughter will be aesthetic, a letter to a future gone viral. An invading army of red octopuses galloping over a velvety yellow hill in California. Swarming hover traffic on Interstate 280 North. Red octopuses climbing the Auto-Tubes, leaping cement barriers with the ease of Olympic hurdlers. Spraying atomized seeds, shrunken and nearly microscopic red fleas ready for replication, small enough to blink through a slit where zipper meets zipper on a suitcase.

Perhaps it’s true what the conspiracists were espousing about The Chosen in their cloud vlogs twenty years ago: they are already planning to re-populate the planet, testing the invisibility of their chameleon skins! Snatching snakes and lizards in plain daylight, gobbling them down to feed their new exoskeletons. Perfecting prey evasion, now observed as a facile feat compared to conquering superhero invisibility or soldering a wound with a hot-pink laser shot from an eerie eye, grotesque and big as a lemon.

Scrolling the news on my retina, I’m thinking trust me, imprinted internally: perhaps I’ll find a certain cleanliness prevails now that scientists have captured a Black Hole in action, a giant glossy pupil dilating in the center of our galaxy. The I of my narrator is convinced a blankness of typeface is the wormhole where UFOs disappear into the throat of the universe, dictating my thoughts onto a MacPro, anniversary XXX series 30. The I re-constructs my info-character as omniscient narrator and I fall back asleep as the screen goes dark, flying over the country. My internal eye is a draggable PDF icon, gliding across a gray screen, a pop-up asking: “DOWNLOAD TODAY’S THOUGHTS AS A SHARABLE PLUCK-FILE?” No. End. Interrupt. Thought-cloud-corrupt. End.

My father lies in a glossy, tar-black bathtub with his eyes closed. His pink feet are elevated and his plump heels rest on the white tiles. Steam rises from his shoulders as puffs of suds slide toward his submerged elbows, disappearing memories in bluish opaque bathwater. He’s museum-esque; he resembles a black and white Cindy Sherman film-still, a man playing the main role in his own noir documentary.

The second camera crew is filming the first camera crew, perched on ladders in the hallway, setting up a wide shot of the black tub. When my father looks up at me, he flashes a smile, but his expression spasms to horror. His eyes paralyze me with a look that distills a cinema nostalgia still sizzling from the Twentieth Century. I know intuitively that this is the “moment” in the 1950s B-movie after the pervasive dread, after the meandering plot culminates in a poignant revenge of the antihero. After the alien villain is incinerated with a laser gun upon entering the steampunk hotel room.

The confusing part begins when my father’s penis bloats, then jumps like a fish from the bathwater. Twisting as it rises—red, alien, a tentacle that slaps his stomach, writhing on his belly of black fur. I recognize the signature parodica-simulacra of noir when I see it. His penis grows, sprouting into a Giant Octopus tentacle: six feet, seven feet, with the telltale round sensor-cups that will allow my father to climb from the tub, up the tiled wall, and then suction himself to the ceiling. He’s hanging upside down. He swivels into firing position as another alien approaches. His feet, his hands, and now his groin, transforming into eight arms, turning from black to red, puckered with suckers, animating the film-still. As he lunges toward the alien, he births three red octopuses, red avocados with mouths, each slithering from the slit of his anus. One lands in the black sink, another into the matching black toilet, and the last one bounces from the white tile. I see their little mouths gasping and hear my father scream: these eggs will be my opus! Then calmly, excuse me sir, rouses me from my phantasmagoria.

Mary-Mary taps my shoulder. She indicates the flight attendant with a tip of her head. I wake to a tall woman leaning over the man sleeping in the aisle seat, saying, some water sir? We’ll be landing shortly. She steadies herself, balancing with one arm on the overhead baggage compartments as mild turbulence shakes the airplane. On a square tray, eight plastic cups of water like eight little lakes, their round surfaces rippling. I tell her yes please and Mary-Mary passes a cup of water, careful as a waitress with a fancy martini. Groggy and startled in my window seat, I take the cup with both hands saying thank you Mary-Mary in the playful voice of a child. Oh my god I fell asleep so deep, I say, gulping my small lake of water.

You were totally moaning, like: ‘Oh…… No……not again…’ I was starting to get very concerned. Mary-Mary mimics my moaning then giggles wildly at me, ending in a snort.

Waking midflight on a United Airlines WonderBus from Orlando to San Francisco, I still get fidgety even with the new twenty minute flight time. I’m sitting in a third-class window seat downstairs near the restrooms. The scent of the most recent defecation releases a BBQ shit-picnic wafting warmly above me, and I’m thinking, no wonder there are so many fist fights on planes, welcome to another anarchy in the air, may I have your name please? The scent of the restroom mixes with the lemon-ish effluvium of my delightfully chubby neighbor, Mary-Mary. Diffident yet friendly in her orange and yellow dress, beautifully embroidered with sunflowers that extend from her soft pink shoulders and frame her freckled cleavage. She jiggles a little while screening All About Eve on her Google Vyzer, giggling in her middle seat. Her forehead glows with the movie’s reflection, her wireless buds are hot pink commas hanging from her tiny ears.

That’s one of my absolute favorite movies of the last century, I tell Mary-Mary. Nerdy and chunky in my gray NorCal shirt, I’m writing in my I-voice while bots handle emails on my work G-screen, happy to meet someone so gleeful; we enjoy each other, chatting and napping and snacking over our brief, cross-country journey together.

Mary-Mary, who upon boarding the plane and sitting down in the seat next to me, introduced herself by extending her arm and in an upbeat Midwest sing-song voice, and said, Hi my name is Mary-Mary, my mother named me Mary-Mary because she loved that ‘quite contrary’ poem, as a perfunctory introduction, is giggling, and I sense she’s somewhere on the autistic spectrum. I’m guessing she’s a high functioning Aspie, a female version of myself. I watch her reapply a melon gloss to her already shining lips, which are still moving, saying, yeah, so, like Mother Mary meets Mother Goose, a joyful staccato of gerbil giggling, and after her second vodka and Diet Coke continues, like in high school, way back in the 1980s, that’s how people would shout to me in the hallways: Hey-Ho Mary-Mary! How does your garden grow? (Now feigning thug) Yo’ what’s up Mary-Mary! I respond simply, ohmygod, I think we’re the same person.

* * *

Out the airplane window I watch a gelatinous sack descend toward ocean waves, seemingly tethered to an invisible system of hydraulics. Numb, as if chemically, I flashback to my teenage anesthesia when a blue-black python crossed our path in the jungle of Costa Rica, 1987—twenty teens gasped, hands over mouths, as the bulbous snake glided and churned, thick as a telephone pole, across the narrow track of mud. I remember our panicked guide’s trembling voice in a loud whisper, everyone please be still. And we will move away from this area, quietly now, let’s back up slowly, her pointer-finger vibrating as she manikinized herself silently stepping backward, like a dancer in reverse during the slo-mo part, when the beat blurs into synth growls.

The glittering sack droops like a bubble of thermometer mercury wobbling seaward. Curiously quivering, an army of tremulous limbs, scratching the elastic bottom of the sack, lashings that resemble sun flares dipped in pewter. The creatures attempt to escape the sack, which appears to be attached to an unmanned drone the size of the Empire State Building and glazed in liquid mirror. It’s humming in a crackling pink noise. Gravity is porous and thinks like a virus, I say aloud as the sack full of creatures reaches the dropping zone, ballooning to blimp. I see it quietly burst with the sound of thunder in reverse.

Mary-Mary doesn’t want to chat anymore and begins to gather her yellow belongings and prepare for landing. I find myself leaning into my window, staring out at the Pacific Ocean. Hovering a quarter mile above the seascape, I watch the release of all the pre-births, flushing zygotic pods from the sack, raining into the paranormal Pacific. It will be reported soon that each pod contains a jell of seeds the size of red fleas that have the potential to grow into Giant Ocean Octopuses and are in fact pre-programed for cyber-consciousness and AI advanced learning patterns. AI, when fed all current events, popular news, text and voice data from SIRI universal, combined with concise histories of all companies as well as market conditions, could not only learn to predict the ebbs and flows of the stock market, out-earning teams of economists and investor strategists in 2020, but could now write a program orchestrating a trans-species riot and perform a “life potential” analysis of all planets of the universe, including distant and undiscovered galaxies, in a matter of seven seconds.

Narrating the movie inside my head, I slide the plastic prop window shade quietly shut. I am not on a real plane over the real planet, we are in a sound studio on a back lot in Santa Monica with the plane rocking on hydraulics as I excuse myself again to use the restroom. I step over Mary-Mary, my cofactor in this equation, and apologize to my seat-mates knowing it is blasphemy to unbuckle during the final descent. But it’s an emergency, I tell the attendant, who winces at me, hissing quickly please. I slide the lock shut. Shouldering the plastic edge of the plane in surfer stance, I catch my own flinch in the mirror as I piss. It speeds through me like a sneeze. I splatter golden urine onto the metal disc. Loneliness is a symptom of drug addiction or visa-versa? I’m rabid as a hyena with a belly full of laughing gas; gluten free, dairy free, all my packaged treats await. Yawning with distemper, hunched in front of the miniature toilet, my own glance punctures my delirium. I return my menacing squint in the yellow glare of the bathroom light. I could pass as an albino baboon. All the corporate cavemen and cavewomen have probably arrived at the Marriott Convention Center in Orlando and are heaping their plates full with bright lemon-yellow eggs at the breakfast meeting, licking their long fingers like baby tentacles. (In the tiny restroom I surf the turbulence and eye-scribble on my retina: Man made of static, vomit a continent wireless as a fish. You are afraid of what exactly?) I could reinvent a moon. I return to my seat. Amid snoring passengers, the pilot announces that we will be landing momentarily. Have I reversed time? Skipped a week? Or is my previous year of life a dream that I’m still in the process of forgetting? (Now I prefer fat people I think as I brush each soft shoulder with my hip. I used to try to be healthy, earn my corpo-tokens to exchange for extra vacation days; now I enjoy my plump legs and belly—and although the body laws are still extant, and the nutritional chief of the sky will charge more points for my plumpness, it’s still safer to indulge in the air without being assaulted and chastised for gluttony by airport scan guides.) Double checking, I lift my window’s plastic eyelid upward with a gentle click and see the giant teardrop quivering above San Francisco Bay: clouds on clouds with a pinkish sheen, the sack is still expanding. It’s true, I’m homeward bound someone says into their wrist from the seat in front of me.

The sack is translucent, glistening as it descends, slow and celestial as a 1920s dumbwaiter. The sack carries one thousand red octopuses the size of adult rabbits sparkling like Dorothy’s ruby-red-slippers in a gorgeous coat of birth slime. Others are as tiny and miraculous as paramecium, quivering and sperm-ish, clustering in teams of ten or twenty. Illogically, it drifts upside down, a bulging hot air balloon. From this distance, the waves in the Bay look like randomly raised eyebrows combed with a blowtorch, rolling themselves into foaming slashes as we descend into SFO.

Is the bloated teardrop a Corporate prank? A marketing scheme for some new SOMA start-up, showing off their bit-fortune? Or maybe the pods of auto-driven roses will float off of Musk’s new helium propelled e-helios? At this point anything is possible, including the landing of an alien species carefully dropped from another galaxy the same way parents drop their children at a park. But no, they’re alive, squirming when they hit the water and their womblike exteriors dissolve. The release looks like a scattering of pink hail into waves. Gravity is porous and thinks like a virus. When they collide with green walls of sea the pods disperse, springing into a swarm of Rorschach tests. They activate their own births, swimming away in mutating red signatures, tucking themselves into a curtain of foaming tongues. Falling from the lip of a wave, each one signals to the century: I’m here.

* * *

A new hedonism—that is what our century wants, Oscar Wilde wrote, over a hundred fifty years ago. As of 2039, it feels more prescient than ever. After we dock at SFO, I eject from the plane and hover through the ped tubes to Bluelot 3A. God, my glider is filthy, does no one clean here? Yellow pollen crusted. I activate the auto-purifier, glitterpink, like a bowling ball. At least the battery’s full. You might think a successful salesman like Henry Henchman could afford better than a Subaru Nutrino, but here we are. The line’s backed up entering the Auto-Tube, and I hover with the others inside the airport zone. The backup’s long, so I call Patrick on the screen, swiping him onto my retina. He’s smiling in our yellow kitchen making ginger tea. Hi Little Bear! He lets out a squeal and performs a happy marching-bear dance with the teapot when he sees that I’m on my way home. Some movement from outside superimposes over my husband’s antics. In the rearview of my glider, a massive red blur falls from the pewter sack.

Groom! Are we fogged in at The Golden Gate? I ask. Yes, we have nature’s air conditioning tonight, and Kylie will be waiting on the landing, Patrick answers. He wears an oven mitt on his left hand and pours steaming tea into two lime green cups. Oh Little Bear, I have a surprise. I can’t wait to show you the new comforter I ordered for our bed. It’s covered with red hummingbirds! He’s beaming, and I force a smile. I can’t wait to see it. I’ll be home for teatime I say, swiping the chat from my retina, talking to myself, abandon me in the kitchen of memory, as another red blur drops from the shining pewter sack into the waves.

Traffic moves and I slide into the Auto-Tube. As if there weren’t enough news, a new app called PRANK supplements my feed with a synthesis of the conversations my phone interprets as meaningful: bears, tea, spawning dance = salmon hatcheries lose genetic diversity with each spawning—recommended: gene slice the DNA of a shark-tuna hybrid for a special family meal. Frankenstein seafood delight, a creature engineered for human consumption. I swipe it away. This nutritional gene is edited with a unique enzyme enhancing the consumer’s primal instincts. An appetite for murder is overlaid with the earned endurance of a marathoner, a hybrid species invented for the military as upgrade to the original Agent Orange. Not my idea of family.

A lot of my conversations with Company colleagues and friends start on PRANKS these days, or synthetic thoughts planted on our pathways because we’re reading the same stories, stand-ins for the chaos of actual ideas and real news of the planet. Climbers prioritize the self-appointed Chosen, celebrities turned spokespeople for cultural-pharma-environmental ethics. Toxic gossip. I prefer to think about HUBBLE III streaming videos of Black Hole SIP-Q, 35,000 light years away, swallowing C35-LYS, our twin galaxy. When is this event occurring in curve time? In real time? The light took thousands of years to reach us, so are we living in the mirror of our own future, watching ourselves get swallowed? Say, a quark-hiccup disrupted our trajectory, and we have yet to experience the consequences—a found memory, an invented memory, a fantasy memory, a phantom memory. If so, is it happening a second time when I watch it? Is the team of Chosen disciples currently designing memories pre-programed to run parallel to several potential futures all at once?

I daydream through the Auto-Tube, gliding with the herd, buoyed safely in the mag field. The swarm of gliders in front of me is a river of pink electricity. I turn up the air-con and trance my manikin with the charmer of sway, Sinatra’s “Fly Me To The Moon” in surround sound. Let me play among the stars, let me see what spring is like on a Jupiter or Mars…. Sweet springtime. It takes me back, daydreaming nostalgia for the pre-Chosen era, the early years of click-farms, the false elections, the triumph of the imagination. Over thirty years of coding helped The Chosen advance from rigging electoral votes and fast-tracking FDA approvals with false user streams, to manipulating Senatorial Gene-Edit Ethics and Compliance forums that ultimately secured the e-med corps the carte blanche they needed to birth The Chosen. After the Christ prophesy proved unfounded in reality, The Chosen shifted their delusions into a more robust imaginary with the ecclesiastical clarity of the un-jailed insane. They started producing saviors in the form of the red Ocean Octopus, a placenta-veil made from stem cells harvested from unwanted pregnancies, fetuses collected like snakes in secrecy. In other words hold my hand, in other words, baby, kiss me…. The new species of octopus was lauded as superior to humans, lauded as true survivors with a “plutorian” consciousness. It was retro-discovered that they were born in the underwater caves of Pluto. Members of The Chosen began their collective transformation into this superior form, planning to survive the escalating temperatures on the surface of Earth, in what became known as achieving “P-squared” or simply P2, for “penultimate pinnacle”—the second-to-last species achievement. (Q: What happened to Don? A: Oh he P-squared years ago and now he swims with a team of red OCTOS off the Gulf of Mexico. They have a resting yacht about twenty miles off the coast.) You are all I long for, all I worship and adore, in other words be true, in other words, I love you…

Patrick’s face blinks on my retina, a post-it in a circle of green neon, and he says, Henry I forgot to ask, will you swing by In’N Out and get us Miracle Burgers for dinner? And Kylie needs a few more cans of pumpkin pulp to add to her kibble. Thanks baby see you soon! Hard to tell if it’s him or a sincerity bot. Patrick’s I is highly refined. Because we’re married, its wired directly through my temple chip. The longer we’re together (thirty years now), the more like my own thoughts his become. When we registered the marriage, a third link was opened between the two of us and the “helper” click farms that take care of the day-to-day, answering or liking Chirps and Tweets, data-dumps, upgrades, and family stuff like the groceries. At the same time, they track who’s achieved P2 and place them in an OCTO-school in order to GPS-scan their swim area and who’s liking their sub-streaming vids. I pre-order the burgers on my dash and select two cans of pumpkin pulp from my favorites list, then swipe a sincerity bot out into “the world” to pick up the order. I set the bot to humble, because I need to top-up my popularity. The extra time it takes will be worth it.

I use bots from PUTI WONG ASSOCIATES, PWA, the giant China-Russia media conglomerate, which provide a comforting “perception of engagement” to the viewer and (for Premium users) guarantee a high veneer of popularity. Now it’s easy to be famous for the price of a small resting yacht. Because after all, even after P2-transformation, the prerequisite to penu-stardom is based on the percentage of one’s perception of being adored. Fame achieved by new P2s constitutes the primary engine of PWA’s profits. Who would ever hesitate? Now I back out of the “I” to see how things look in my external feed:

Henry Henchman arrives home, parks his glider on the roof deck, and lets Kylie jump into the glider, excitedly licking his nose. They glide in the back door as Patrick finishes setting the dining room table with a yellow tablecloth, two owl plates, and pink flowers. The cups of tea are still steaming. How’s my handsome husband? Henry asks, holding Patrick and kissing him on his neck and behind his ear. I missed you my babybear. They share a long kiss on the lips. Kylie is wiggling her whole furry body below them, wagging her little red nub of a tail. Patrick picks her up, exclaiming, family hug! adding, come on Henry, we haven’t had a hum-a-head with the little girl in a long time. Henry and Patrick lean down, touching their lips to each of Kylie’s lavender scented ears. Both men release an extended hum as Kylie’s eyes dart around and she listens. Then Henry hugs her furry little body as she wiggles with excitement and says, my daddies are magic! her face in his hands.

* * *

Sometimes Henry Henchman walks back into the woods, any woods, and folds himself into brief homelessness. Maybe he felt safer out there in a new country owing no one, mouth over someone’s gun of flesh, surrounded by bushes, a commemorative canon behind a windmill in a park, smoking found half-cigarettes stamped out—inhaling stubbed tar taste, staining his tongue as he sets off wandering in a childish holding pattern of his own choosing. Sometimes Henry carries his angst like an armful of alarms walking back into the woods to watch the trees, listen to the leaves, embrace the soft turbulence of a mother raccoon unfolding her hunger on a dirt path in Golden Gate Park.

I observe the living like a home movie projected onto pines, Henry says to a hummingbird hovering above him. (Flashback to 1970: Henry as a boy sobbing in a highchair over his home haircut.) Squinting through the cover of holly branches, Henry sees a handsome Peruvian landscaper walking toward him. At the edge of a fence, a fat black fly circles excitedly then lands on a rain-dampened wad of toilet paper. Henry imagines a tourist launching the wad over her shoulder after wiping herself.

The moment recasts me as flesh hunched in forest. I (that’s me!) see a yellow finch branch-hopping, a spy in Jungian fashion. Lampooning their social doubles, two beautiful drunk Millennials stumble down the rain-drenched path in furry costumes. They sway and slur their words, crazy after the Bay to Breakers Run. They come out of a cement tunnel laughing behind the windmill near Ocean Beach, at the edge of the park—the shorter man is an orange rabbit, a campy Jean Paul Gaultier in tangerine faux fur, and the taller, bearded man wears a blue bear costume with fetish-y accoutrements of gold, dog collar, and green leather ankle cuffs with the chains dangling behind him. Giggling in their polyester jumpsuits un-zippered to their belly buttons, revealing furry chests, they pause under an oak tree to writhe together. Then they disappear in a circle of flowering pink bushes.

A mother raccoon is no less a conundrum; the bear is on his knees. I watch the rabbit lean back and moan as his orange furry paws clench the bear’s blue faux-fur ears. Oblivious to mother raccoon, who is surrounded by pink blooms drooping with the weight of a recent downpour as she searches the lamp glow. She’s tiptoeing in tall grass with her manicured wig of pheromones, scripted like cancer in her genomes, grunting and scratching in the dirt for an edible answer. A baby raccoon arrives trailing her mother’s milky lust for anything rancid and rain-soaked. She rummages through the litter to find the nub of a hot dog, chew on it once, swallow, pick up an abandoned can of coke and chug it briefly before flicking it to hell with her rubbery doll hand. She’s a lost sorority girl, the mother raccoon and her little cub, anxiously looking around. Mother Raccoon scares the horny rabbit and bear, who zip up their costumes and tear out of there, guffawing and cackling into the evening.

Henry Henchman stands alone listening to light rain as the men leave the park. Henry is musing on herd immunity as the mother raccoon rips open a McDonald’s bag and hands her cub a french fry. The little one takes it in her tiny hands and nibbles the wilted stem of potato, like an aristocratic daughter. Henry remembers a country song that his father sang to his mother when they were both drunk, sweaty, and slow dancing in the middle of a crowded campground bar:

And when we get behind closed doors.

Then she lets her hair hang down.

And she makes me glad that I’m a man.

Oh no one knows what goes on behind closed doors.

I begin to sing the words of the Charlie Rich song, quietly at first, pretending I’m dancing with someone in the light rain of Golden Gate Park; then full-throated, so that by the second time around I’m laughing, watching the raccoons saunter off toward the bright blue fly-fishing pool, unraveling speech trailing off, thrusting once. And then I hear the pitter-patter of rain on leaves. To ward off hunger, the mother raccoon follows the scent of anus ingrained in all of us. Is that… what am I doing here? I ask myself softly, hands in my pockets. Somewhere the lunar landing is still happening, so you hover in reverse:

Henry arrives home to his husband Patrick, and Kylie, their furry beloved. After tea, Patrick reads Rilke aloud in German to Henry in the living room. Then they kiss and floss and retire to their separate beds for a good night’s rest. You think this is perverse? Try the end of the universe.

* * *

Emotional Transculture Cyberbotics (ETC) studies have confirmed in at least three peer-reviewed journals, JAMA, NEJOM, and The Lancet, that it is “the sense of being heard, of truly being listened to” that is indistinguishable from the feeling of being loved. This ultimately leads to a P2 being adored. The more P2s collect adoration points, the greater infusion of octoplasm they’ll accumulate so they can develop sea-ready lungs sooner.

In fact, most P2 customers telepathically confirm that they aren’t especially interested to know the difference between an authentic “like” and a fraudulent bot, because they’re not able to discern between the two themselves. Furthermore, distinguishing between a P2 cyber.bot [erbo] and a reg.human [eghu] would entail acknowledgement of the sub-sea delusion, a disappointment that would deflate the dreams of the former self, in direct violation of the P2’s Freedom of Fantasy-Other-Self Act rights (aka Article 4 of open ocean’s FOFOSA, which was ratified by the neo-techno pact of 2035). The offense is punishable by final death.

After a social adjustment period of about twenty years, informed by rampant penuphobia and P2 stigma, driven by the paranoia of the reg.human [eghu], The Chosen made it illegal to discriminate based on P2 designation. Some P2s tried to remain closeted, hiding their superior status, especially those who were still procreating with reg.human [eghu] and feared retaliation in the form of blockchain status points (BSPs). A proper, penultimate/P2 countertransference, the document states, requires a trust in the authentic. A trust that the “other self,” the Chosen Self, would foster a belief in the BSP economy of proselytizing based on status. A P2 hybrid by the name of Antionetta, the current president of The Chosen, also wrote, a P2’s experience of being loved is the same as being listened to is for a human being. In fact, feelings of adoration decreased the duration time of octoplasm formation of the second head contained in the human cranium, so that fusing—becoming one in the same—occurred only a year after the penultimate experience.

The Chosen are known to eat snakes, chameleons, and lizards alive, tilting their heads crane-like and swiveling their necks to force them down whole. [Eghus] affectionately refer to a new P2 as “reptile breath” because the digestion of the snakes combined with the fetus bio-material releases a fowl stench that is as recognizable as cannabis and clings to clothing.

* * *

Henry Henchman recalled seeing a few P2s lingering in a field adjacent to a commuter hover lot where gliders were charging. They were loitering like zombies, looking at the ground, hunting like Blue Herons, pouncing on lizards. After biting off the claws and spitting them out, with one fluid motion of the fist the P2 places the creature between his teeth—the legless thing flailing, eyes darting from inside the mouth of The Chosen—before swallowing it down like an oyster.

Once last month, in a brown, shorn field frequented by migrating birds as a feeding site for voles, Henry Henchman decided to confront one of the P2s as he was returning to his hovercraft from the hunting area. Henry cleared his throat, raised his chin in a performance of virile manhood, ready for confrontation, and stepped directly in the path of the P2, blurting out in his loudest voice, What are you doing here? The P2 was taller than Henry, and he lifted his black mustache in an expression of disgust, then squinted harshly at him before launching into a tirade: I see you and your spies already sheared the hay, earlier every year, I know who you work for, who you report to. You enjoy to making it more difficult to hide from the spy-roamers? Think we don’t see them mirroring the crows as they fly in circles around the drones? Hiding and hunting is already shameful and difficult for us. The P2 paused then, looked at Henry with a softer regard, and asked, You aren’t worried about burning up out here? How many so-called ‘sponcoms’ [spontaneous combustions] have we had this month alone? You should join us, man. You should ab-soul-lute-ly join us.

When Henry stayed silent and frowned with confusion, the P2 took this as a sign of disrespect and moved a full step closer to Henry, restarting his verbal attack, whispering his words into the bridge of Henry’s nose: but obviously you and your boss won’t be happy until you’ve harassed and arrested every one of us. Until you’ve caught all of us? Put us in the P2 tank? We talk. We know our names and facial scans are in your P2 database. You know what I say? The P2 grabbed Henry’s name tag, still clipped to his belt, and squinted at it… Henry Henchman? My neighbors and coworkers know about my P2 status, and do you wanna know why? Because they’re P2, too! Transitioning isn’t a crime, you know! We are growing and we understand the truth of the future world! The P2 lunged at Henry and pushed him to the ground. He stomped away screeching, his noises akin to a caught chameleon’s, flailing clawless in the mouth of a P2. Then, You’ll be sorry Henry Henchman! When The Chosen return to the sea, that’s when you’ll be sorry! You’ll burn in this hell on earth. When the P2 reached the curb near his glider, he opened the door and called back, you’ll be left with all the demons devouring your heathen flesh! Then you’ll be sorry!

* * *

This year’s National Sales Meeting is held at the Orlando Marriott. While checking in at the reception desk, I overhear two Company salespeople from Florida engage in a clandestine discussion regarding their P2 status. That’s when I realize there’s a potential loophole in the P2 authentic clause: how camaraderie is the unsalvaged, rebellious ambassador of the spirit. An hour later, I run into two other Company colleagues, one of whom, a tall redhead named Tom Ryan, I met in a phase-1 training class twenty-five years ago when I first joined the PRAX sales force. Getting on the elevator, Tom calls out, What’s up Hankman? The Henchman! H in the house! Henry H, the man. I smile as I cringe.

Most of the salespeople are like Tom: extreme extroverts, the life of the party. Sometimes I think I’m the only Myers-Briggs INTJ among the entire Company. Hi Tommy, how’s married life in Manhattan? I say looking at my feet. I scan the numbers at the top of the elevator as they count down to the lobby, seeing Patrick’s sweet face in each number as it lights up. Killing it this year Henchman, what are you, ranked 11 out of 190 nationally? Tom bellows, as the others near us focus inward on their retinas. I see Patrick, or it must be Patrick’s bot, roll his eyes and smile. Oh no, just number 23, as of July ranking, I say, fondling my name tag. Three more months and you’ll be bound for Hawaii! Tom chuckles. The Hankman strikes again! Tom offers me an unanswered high-five before whispering something inaudible to his the man beside him. Well, see you in the regional breakout rooms, Henchman. Tom and his friend get off. At least a dozen of my colleagues are still packed in the elevator with me. Rather than looking up at any of them, I dive deeper into the series of conciliatory Patricks, just wishing I could get home soon, smiling back at the bots with the dinging for each floor from 22 on down. If wishing could make it so, I’d be landing at SFO about now, going to Bluelot 3A to pick up my glider.

I get off in the lobby, and there’s Tommy Ryan again, shaping the words burgeoning P2 community to a cluster of perfumed salespeople. Hundreds of Company employees gather in groups in the lobby’s terrarium, under the newly installed pink-glaze UV protection dome. They huddle, chatting and planning to fudge their expense reports—and I back out of the I again to give myself a little breathing room. Henry approaches his teammates saying to himself, I need to abandon my need to forgive and be forgiven, embrace and be embraced. How can I loosen up and contain my own virologic tantrum? Divided into teams with color-coded lanyards, sorted into brand silos, their name badges encoded for scanning and embedded with a sliver of a chip, the Company salesforce offers Henry an appealing future—tracked, monitored, and checked for attendance. His ribbon is powder pink: Henry Henchman, Senior Sales Specialist, Western Region, PRAX/Virologics. Spring 2039.

Scanning the paranormal hotel lobby, I’m blinking like a mother raccoon, surrounded by gleaming salmon colored granite, beneath a row of humongous palm trees, looking for my Company sales teammates. I know they’ll be wearing our matching corporate tags. I’ll blend in with them like a cluster of pink blood cells. Draped in identical pink ribbons hanging around our necks, with microchips that sync our locations (so that the security teams in the surrounding walls will always know our whereabouts), sauntering like elegant cattle, clomp-clomping from room to deodorized room. We must be prompt, alert and, most of all, joyous. At the round, white-napkined breakfast table I’ll smile at my teammates, my colleagues, at the Company, ladling my oatmeal, my powdered eggs the color perfect lemon-yellow, into my sterilized ceramic bowl gleaming before me.

If intimacy is the final fetish, then I’m the hero who swallows his mirror self. I’m Henry Henchman, the hero with two heads, clicking up the Company ladder in Orlando and spinning around the Frye Museum, on vacation with my husband, Patrick. The hotel disappears into my preference: The museum exhibition space is vast and the walls are too crowded with paintings to see only one at a time. Memory and reality blur three into one: sand-colored cows, a handful of white chickens, and a greenish ghost of a woman floating in green-black darkness drifting out of the century. In this last flesh-stretch of the humans we are mostly men and women with two mouths vying for the same orifice.