“What’s good?” from the other side.

Great news: I’m alive and well in living color… just not in the way that you are used to… and for that I’m sorry.

Did you get my message? The one left near the body I chose to leave behind?

It’s been lonely… and I might not be there now… but I’m always with you.

Category: Uncategorized

-

Poem

-

Six Poems – Bernadette Bowen

WE ARE ALL SURFACES IN THE ENVIRUSMENT

WE ARE ALL SURFACES IN THE ENVIRUSMENTMy love

Hangs around

Like mold.I Infiltrate

Your porous

WoodSink into

Your

Remembrains.—-

Don’t

Mind me……Just evading

Lapses to

Rid your

Infrastructure

Of me;Fortifying

Myself

—Stronger

Than ever

Inside You.—-

I am the

Twenty-percent

That know

How to

SurviveYour vinegar.

—-

Undetected

I cunningly curb

Your interestTil you’re

Cupping at

The seems.—-

Curve for me.

Show me

How

Your heatThat

Grows meCannot

Contain

Itself thereInside your

Surfaces.—-

Allow me

To snake

Through

your veinsLike water;

Weaving

Through

Your textures,Tainting Your

Would boreds,Inking them

With life.—-

Isn’t it

All So

Exhilarating——How Even

My most

Toxic

Release of

Sporesbeats

The drone

Of yourTidy

Polished

Home.I HAVE BEEN WADING

On the

Ocean of

Missing you

For So Long,I’m getting

Scurvy

Over here.—-

I have the

Cabin Fever of

Missing you.—-

The Creatures

Of usLive on in the

Deepest parts

Of my memorseas.Not a day

Goes byI don’t

Hold my breath

To Dive back in

And pull them out;Basking them

in the sun

Of mynd’s surface.—-

Our sea monsters

Shine brightly when

Allowed in daylight.—-

I’m keeping

The map;Charting course

To our

Buried treasures.I haven’t

Forgotten

Where

X markedOur spots———-

—So Many Times.BALDILOCKS BUMBLER VIRTUOSO

Watch me

Blow thought

Bubbles into our

Re-space-o-ship.—-

Since You Shut

Your Electricity off,The pixels of me

Still spend all theirTokens and free time

Grinding, Bouncing, &

Reflecting in Our lights.—-

A play palace

Despised, I~backstroke~in the

____ball pit____Full

———Of our gazes

——into each other.—-

Though you stopped

Paying admission,The bare moments

of us—-Still Dance|||Encased||| in their

<<<>>>

<<<>>> [Turns out,

This space was

Always

self-sufficient].The show

Must Go On.I’M HERE TO(O)

Fetishize

The face.Face it,

I do not

Miss

Any–-But

Yours.—

Take off

That maskSlowly

For me.No need

To be Shy

Or coy,I know

What’s under

There.I’ve seen it

All

Before.—

Show me

AgainHow you

You.It’s been

So longSince

Anyone

Worth

Looking

AtHas Looked

At mePhysically,

Viscerally,

in My

Direction.—-

Before our

Total Dark

I mourned

Our sight lossLike

I hadMy childhood,

Dog.I knew

We

Were going,So I

read booksIn place

Of

Your faceTo Supplant

Our Deterioration.I Wrapped myself

In The Comfort

Of fiction,Between covers

and frayed spines.—

Shipping

Is delayedOn shared

smirksIn the

Unfor-see-me-able

Future.—

In this

Envirusment,We are

Flesh and

[Thus,]

Fresh Outof

Knowing

Glances.—

I see now,

There is no way

To Properly grieve

the Relishmentof your

Idiosyncrasies,As we are,

Relegated

To only

A Past-time.YOU WERE NOT ROUTINE DENTAL WORK

The worst Part

of losing you

is that _________

___________

_____________.—-

Not some

Superficial filling

I could replace.You were that

Real enamel Deal.—-

Over the years,

I’d developed

Quite the sweet

Tooth; taking

Bigger Bites than

I Could chew.—-

I ached from

Your erosion

For Months;Numbing myself

Preemptively

For Your extraction.—-

You Didn’t

leave a

minor cavity.I required

A full-blown

root canal.My nerves laid raw in

the deepest parts of

me from your loss.—-

You were ripped

from my mouth

and placed back

into that of another.I have

No right

to be sadOnly sad writes;

Gumming at

Our leftovers.THE BABY

Words in

My brain

Are crying

Out of me.They say

It’s time

For themTo be

Birthed

Out from

My Mental

Holes &Into the

—World.—-

Words

Have no

Need forSucking

Their

ThumbsTo self-

Soothe.They

Are the

Food &

The Shit,& We—-Are

The Worms. -

Me and Bobby Kennedy

1

I never formally met Bobby Kennedy, but I did once alter the course of his life for maybe five minutes. Since then, I have always felt a certain kinship with him. Had he only lived longer, who knows what he might have achieved.

I never formally met Bobby Kennedy, but I did once alter the course of his life for maybe five minutes. Since then, I have always felt a certain kinship with him. Had he only lived longer, who knows what he might have achieved.My relationship with him began on a beautiful fall afternoon back in 1964, less than a year after his brother, President John F. Kennedy, was assassinated. It was a few weeks before Election Day, when President Lyndon Johnson would be running for a full term, and Bobby Kennedy would be running for senator in New York State.

I was hanging out in the storefront clubhouse of the Eleanor Roosevelt Independent Democrats on the Lower Eastside of Manhattan, trying to figure out how we could distribute piles of cartons of campaign literature. We had all kinds of neighborhood characters dropping by, sometimes giving us political advice, but rarely offering to help out.

One of my favorites was an elderly man with a long white beard, who told us his name, but then confided that everybody called him “Uncle Sam.” I can still remember two of his sage observations.

“You want to know what is wrong with the name of the Republican Party?” he asked, while rolling the “R” in Republican.

“Sure.”

“Re means against; public means the people.”

“Great!” Carlos observed. “The Republicans are against the people!”

Smiling at his bright pupil, Uncle Sam was ready to disclose his second observation. “Do you know what is right in the middle of the Democratic Party?”

We all just shrugged. Uncle Sam waited, wanting to give everyone a chance to guess. And then he told us: “The Democratic Party has a rat in it,” again rolling his r’s.

We just shook our heads. The man was perfectly right. We invited him to join our club. As he left, he said he’d think about it. But in the meanwhile, we should consider changing the name of our club. “Eleanor Roosevelt, she is a living saint. But think of getting rid of ‘Democrats’ from your name.”

2

As much of a character as Uncle Sam was, he did not come close to Mrs. Clayton, who burst into our office one afternoon and demanded to know where our Robert Kennedy glossy photos were. Indeed, where were they? We all looked at each other and just shook our heads in shame.

“Are you trying to tell me that you don’t have any?”

We sadly agreed.

“Can any of you please answer this simple question? How can you call yourselves a Democratic club if, just weeks away from the election, you don’t have any of Bobby’s photos?”

Mrs. Clayton was a very nice-looking Black woman, maybe in her mid-sixties. And she seemed quite comfortable expecting answers to her questions. But I couldn’t get past wondering why on Earth she was wearing a fur coat on such a warm day.

“What? Do I have to do everything around here? Who’s going to drive me up to Kennedy’s headquarters on 42nd Street?”

None of us had a car. “Mrs. Clayton, if you can get some Kennedy glossy photos for us, I’ll be glad to take you up there in a cab.”

“You’re on, young man!”

3

Fifteen minutes later we arrived at a large storefront that served as Kennedy’s campaign literature depot. There, I saw cartons piled eight or ten feet high along the walls and a whole bunch of people, most of whom looked very busy. I heard quite a few Boston accents among them.

Mrs. Clayton walked in as if she owned the place, and for all I knew, maybe she did. She buttonholed a middle-aged guy with red hair and the beginnings of a potbelly, and told him that she needed a few carloads of Kennedy campaign literature for this boy’s club on the Lower Eastside.

“Who yah with?”

“The Eleanor Roosevelt Independent Democrats.”

“Never heard of ‘em.”

“We’re on the Lower Eastside. We’re a Reform Democratic club,” I replied.

“Oh, we already sent a whole pile of stuff tuh the Regular Democratic club down there – the Lower Eastside Democratic Association. Why don’t you get some from them?”

“Are you familiar with the Hatfields and the McCoys?”

This got a big laugh out of him. “Mrs. Clayton, you can take whatever you need.”

He called over a couple of guys to help us, and a few minutes later, Mrs. Clayton and I were sitting in the lead limousine in a caravan laden with enough Bobby Kennedy glossies and other campaign material to give out to every Democratic voter in the entire city.

When we got to our clubhouse, Kennedy’s workers and our own people quickly filled up our entire space from floor to ceiling. When they were ready to leave, Mrs. Clayton‘s parting words to us were quite direct, “When you need something, all you’ve got to do is ask for it.” Then, she got back into the limo and rode home in style.

4

After Mrs. Clayton left, the rest of us started going through some of the cartons. Whatever else might be said, there surely were enough Bobby Kennedy glossy photos, many of which showed him with smiling crowds of people. But there was far too much campaign literature for us to use, even if every household got dozens of different pieces every day.

“What are we going to do with all this shit?” asked Martha

“Hey, I’ve got a great idea!”

Everybody looked at me. While I was apparently the quasi-leader that day – not to mention the person who’d helped Mrs. Clayton deliver the goods – they were hoping that I was serious.

“Let’s dump whatever we don’t want in front of our dear neighbors, the Lower Eastside Democratic Association. You know, when I was at the Kennedy headquarters, they told me that those bastards down the block froze us out of our share of not just the Bobby Kennedy glossies, but of all the rest of his literature. So wouldn’t it be poetic justice to dump what we don’t want in front of their clubhouse?”

Thankfully, cooler heads prevailed, especially since, without a car, it would have been some job carrying all those cartons. And we might have even gotten arrested for illegal dumping.

“OK,” I agreed. But we need to make a good faith effort to distribute as much of this as we can. I really do hate to waste anything. And also, dumping this stuff would not be fair to Mrs. Clayton.”

So, we all went back to going through more of the cartons. After several minutes, Harry called out, “Hey, what should we do with these?”

He read us the title of a stapled packet of printed pages: “Senator Robert Kennedy’s Address to the Mizrachi Women.”

“Who the hell are the Mizrachi Women?” I asked. I’ve heard of Mizrachi salami.”

“Don’t they carry that brand at Katz’s Delicatessen? Maybe that’s what they’re referring to on that big sign they have on the back wall,” suggested Carlos.

“What sign?” asked Harry.

Carlos was laughing so hard, he had to hold up his hand for everyone to wait till he could speak. Then he said, “Send a salami to your boy in the army.”

Now we were all laughing.

Finally, after we had all settled down, Martha explained that the Mizrachi Women were a Zionist group that promoted education in Israel. That certainly seemed inoffensive enough.

I said that I was uncomfortable about distributing this twenty-page handout because it appeared to be pandering to Jews. “Look, I’m obviously a member of the tribe, but I think that while it’s fine for Kennedy to address this group, distributing it may be going a step too far.”

“So should we just dump them?” asked Martha.

“I have a great idea!” declared Harry. Let’s give them out to people on the street, but only if they’re obviously not Jewish.”

“Sounds like a plan,” I agreed.

That evening, as I locked up, I felt we had gotten a lot done, although now we had to get rid of all that shit. On my way home, I saw a middle-aged Black couple standing under a street light. Their heads were bent together, but they weren’t talking.

Then I noticed that they were thoroughly engrossed in something they were reading. It was Bobby Kennedy’s address to the Mizrachi Women.

5

The chances are, you never heard of Samuel Silverman and you’re not at all familiar with the Surrogate Court of New York County, aka the court of widows and orphans. Each borough of New York City has two surrogate judges, who appoint lawyers to handle inheritance cases of families who can’t afford their own legal representation.

So that’s a good thing, right? Not always. And certainly not in the surrogate courts of New York and many other cities. Often lawyers, in cahoots with the surrogate judges, charge very high legal fees, depriving the widows and orphans of most or all of their inheritances.

In 1966, Senator Robert Kennedy decided to put a stop to this practice at least in the Manhattan (New York County) Surrogate Court. Looking long and hard, he finally found the right man — Samuel Silverman, a justice of the State Supreme Court.

The patriarch of the Kennedy clan, Joseph Kennedy, had amassed a family fortune that would be equivalent to at least ten billion dollars in today’s dollars. His hands were far from clean, but he provided his sons with seemingly unlimited funding to run for high political office.

And so in turn, Bobby Kennedy funded Justice Silverman’s campaign in the 1966 Democratic Primary for a vacant Surrogate seat. Almost no one in the entire borough of Manhattan had ever heard of Silverman, let alone had any idea of whether or not he might be a good Surrogate.

But none of that really mattered. What did matter were Senator Robert Kennedy’s endorsement and Joseph Kennedy’s money. But Bobby certainly put his father’s money where his own mouth was. He campaigned tirelessly for Justice Silverman.

6

One Sunday afternoon in late May, just a few weeks before the Democratic Primary, Bobby Kennedy, accompanied by Justice Silverman, was scheduled to tour the Lower Eastside, making stops in each neighborhood. The tour would culminate in a giant rally in perhaps the busiest intersection of the entire Lower Eastside – the junction where Essex Street and Delancey Street met.

When the caravan arrived in front of our clubhouse, there was Bobby Kennedy sitting in a huge black convertible, and sitting next to him was Justice Silverman. Both of them were smiling and waving to a lively crowd and even reached out to shake a few hands.

The problem was that they were more than an hour behind schedule, and had been long overdue for a rally before what might be the largest crowd in Lower Eastside history. When I approached the lead limo, the driver told me to hop into the front seat.

“We already got lost three or four times. These damn streets don’t have any numbers like they do uptown.”

“Hey, Boston’s even worse,” I replied.

He laughed. “You got a point there.”

“So you want me to be your guide?”

“Absolutely! We got one more stop to make – the Lower Eastside Democratic Association.”

“OK, I said. They’re just down the block, but if you’re really in a hurry, I know what we can do to save some time.”

“You’re the boss!”

We slowed as we approached their clubhouse. They had a small crowd, and when they saw Bobby, they went wild. They were expecting about a five-minute stop so that Kennedy and Silverman could each say a few words and maybe shake a few hands.

But I told the driver to speed up and I’d get him to Essex and Delancey in less than two minutes. When the people in the crowd realized that we weren’t stopping, some of them starting cussing and shaking their fists in the air. I looked back and saw Bobby and Justice Silverman laughing. When he caught my eye, Bobby gave me the thumbs up.

At Essex and Delancey, the police cleared a path for our motorcade, and Bobby and Justice Silverman climbed a ladder on the back of a large flatbed truck. There was an elaborate sound system, and despite all the ambient noise, Bobby could be easily heard even blocks away as he addressed the crowd.

I could not believe how many people were there. Traffic was completely cut off for as far as I could see, and there must have been several hundred thousand people covering every square inch of ground.

I got out of the limo and read the label attached to the ladder. It said, “Property of Joseph Kennedy.”

Meanwhile Bobby was teasing the crowd. Of course, he knew why so many people showed up. There was just one person they wanted to see and hear, and regretfully, that person was not Justice Silverman.

I remember his saying, “I know that all of you have been standing out here in the hot sun waiting to meet Justice Silverman…”

There was a vast roar of laughter. Nobody had ever heard anything that funny. They would probably remember that remark for years. I certainly did.

It didn’t really matter what Bobby said, or what Silverman said that day. Many of those people would vote for Silverman just on Bobby’s say-so. In a few weeks, Silverman would win in in a landslide.

7

Two years later, the Reverend Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy would die from assassins’ bullets.

And now, after so many decades, I still cry whenever I hear Dion’s mournful song, “Abraham, Martin, and John.”

Here are the last four lines:

Anybody here seen my old friend Bobby?

Can you tell me where he’s gone?

I thought I saw him walkin’ up over the hill

With Abraham, Martin, and John. -

Poetry Holiday Grab Bag NYC

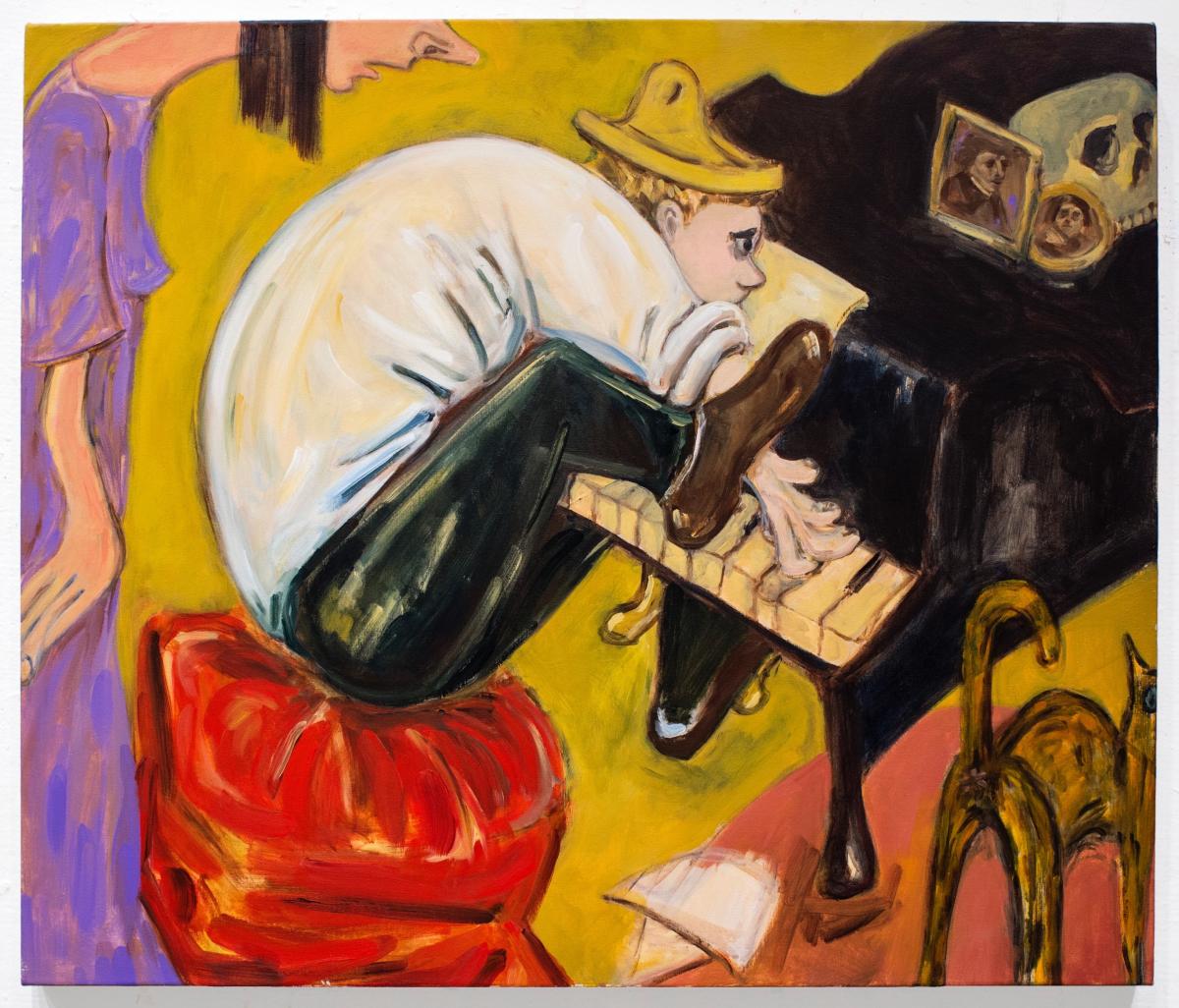

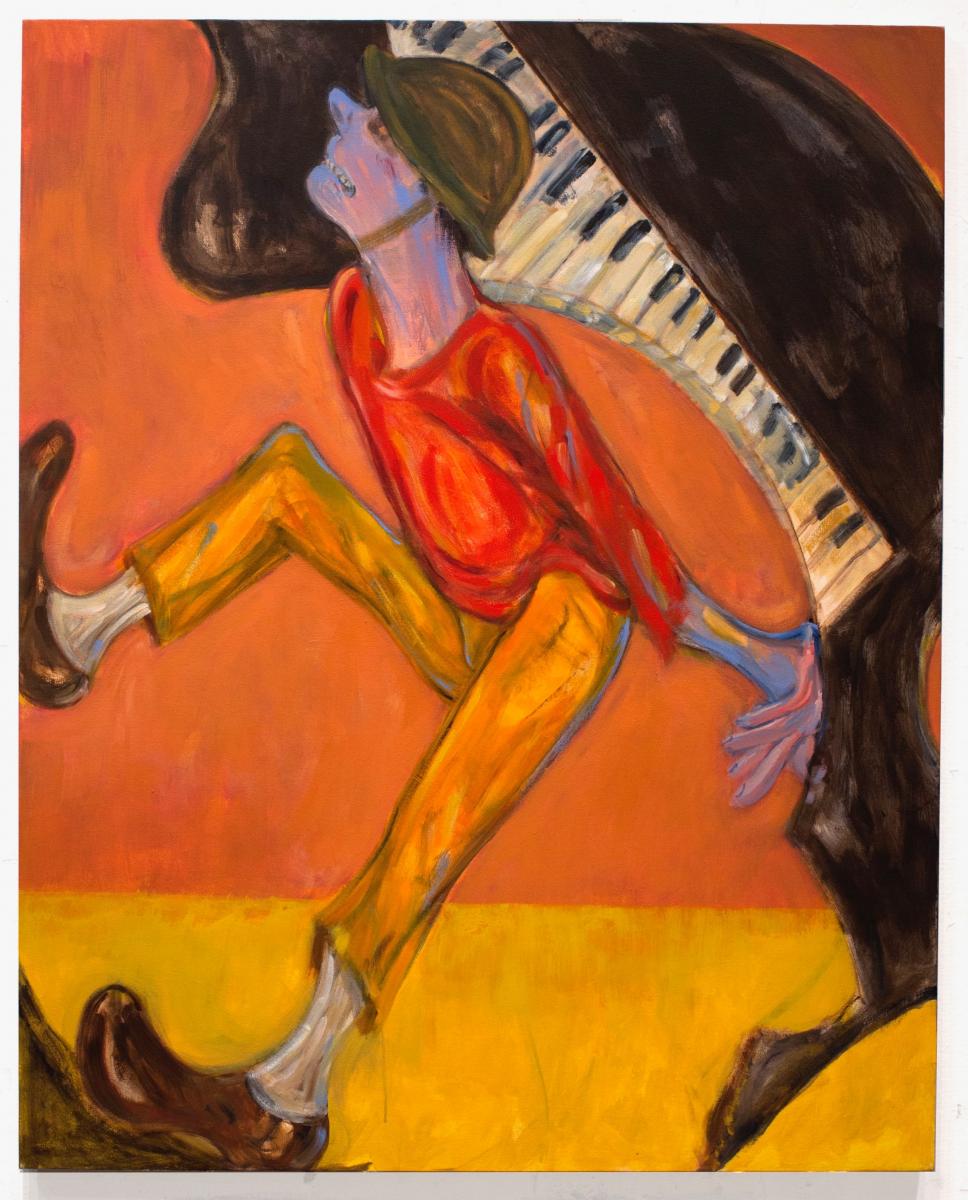

New York City PoemsBy Francesca MaraisShortchanged 5th Ave Blueshis hands stroke the warm brassas his fingers orchestrate a sultrynumbahthe dehydrated leaves now Halloween orangebegin to confetti from the treesnext door Central Park playing piperto the stoopers moochersMET and museum enthusedwhile their arms whip for their phoneshis lips purse into harmonies that couldput a snake to bedthe stoopers crowd the staircaseand passersby confetti changeover a hathis posture adjusts in anI-will-not-be-reduced-to-a-dollarNew York at his feetunexpectant and lifted, his crowd’smouths speak a quiet breezethey envision a viral uncovering ofnew-found-New-York-jazz-manhis image doubled in vivo andInsta-televised on the latest iPhonezooming in from the top staircasethe musician now a 45 degree benddipping into his well of historyhe kneels into a crescendothe cameras, magnets gravitatethe musician towards them andthe shot is reeled inour jazz man’s pursed hum frownseven though the melodiessing a joy from his youth and ofdeep love for his woman his familyhis citythe hatbegs to be seized and anotherphone captures the blisteringsynthesized tuneswe envision a 10k followingdiscovering uncovered groundjazz a new beat only foundin the city whereeveryone comes to eathis back turns and we losethe portrait but his pain is therehis clasping fingers pressing

New York City PoemsBy Francesca MaraisShortchanged 5th Ave Blueshis hands stroke the warm brassas his fingers orchestrate a sultrynumbahthe dehydrated leaves now Halloween orangebegin to confetti from the treesnext door Central Park playing piperto the stoopers moochersMET and museum enthusedwhile their arms whip for their phoneshis lips purse into harmonies that couldput a snake to bedthe stoopers crowd the staircaseand passersby confetti changeover a hathis posture adjusts in anI-will-not-be-reduced-to-a-dollarNew York at his feetunexpectant and lifted, his crowd’smouths speak a quiet breezethey envision a viral uncovering ofnew-found-New-York-jazz-manhis image doubled in vivo andInsta-televised on the latest iPhonezooming in from the top staircasethe musician now a 45 degree benddipping into his well of historyhe kneels into a crescendothe cameras, magnets gravitatethe musician towards them andthe shot is reeled inour jazz man’s pursed hum frownseven though the melodiessing a joy from his youth and ofdeep love for his woman his familyhis citythe hatbegs to be seized and anotherphone captures the blisteringsynthesized tuneswe envision a 10k followingdiscovering uncovered groundjazz a new beat only foundin the city whereeveryone comes to eathis back turns and we losethe portrait but his pain is therehis clasping fingers pressinginto it with another sound and

his eyes hover over hisshortchanged hatA warm bowl of kitchari to teach you to sit stillDieting is the second highestcontribution to consumerism.Go figure…but unlike the rest of the21 day programs and elimination ofthis, that, and try a keto diet,fast intermittently, give up eatingwhile-you’re-at-it diets, fads.This is a lifestyle, humbling mewith its rice and grainsingraining memories of the warmingmeals grandmothers’ hands made,waking a sleeping me by crowing cocksomewhere on some farmfar away from these concrete slabs.The slow rush to greet the hidden sunbehind haze over the Hudson, united meto my thoughts of hungerfor something deepera meal nor my tastebuds couldn’tdistinguish – cheese,honey, chocolate, not even gum,no.Not even wine crossed my mindas I moved slowlyin the race to transformmy mind and body.Given up on the demon andangel trumpeting in my earsas I chugged a beer or shut the alarmor ate a cookie after a bowl ofsalad.I gave thanks for the bowlof kitchari more deeply,in wonderment.I obsessed with the floatingnotes of a jubilant spice market.Hail melteddown my cheeks asmy nose caught a whiff of the warmbowl of kitchari.I heard the angel speak to thedemon asking when I’d grabfor a slab or a pint.My hands fidgeted with anythingthey could find to quieten the noise,and I laughed alone outside myselfrecognizing the fixation for moremovement in and around me.Beside myself with wet face andstuffed mouth; I thoughtmad or suffering withdrawalswas I, butjust realised all thechannels were turned onwith the volume maximized.born again.Times SquareBeams on the empty streetsI don’t even recognizeThe echoing of the sparse yellow cabIn the distance, honkingBarren sidewalks whereI walk down directionless,No one around to shuffle past,Bumping in to remind meThat time waits for no one in this cityWhere everyone comes to eat.How long has it been sinceyour birds were able to sing? SinceThe fish jumped out of the East RiverTo come up for air? Since your skiesWeren’t shadowed by the remnants ofCongested roads on the Holland-TunnelOr Washington Bridge, trying to make itTo work on time or back home for dinner?Since I didn’t need to screamin conversation to my friend next toMe on the subway? Like you, ManhattanWith your surging energy,I survived on Laughing Man coffee toFuel me from my day jobTo my effervescent East Village –Williamsburg parades, onlySleeping to sober its memoryLike you Manhattan, I thrived in theSpaces foreign minds like mine connectedOverlooking the New York skyline at aLimited pop-up happy hour venue,Recalling the names of the tenNew faces while swimming in theTiki themed cocktail menu I’ve consumedI need the noise to drive me so I don’t have to find what ignites me And potentially fail at it without even having triedI need the noise to drive me so I don’t need to face that I came Here without purposeAnd you’ve worn me outI need the noise to drive me so I don’t feel lonelyIs that how you feel? Now that all the PetersWho called you home, have left now?You are free from entertaining a storyYour trees can now breathe.Burnt stub“Talana,”That was the name of our teamAnd I was maybe six or seven,Bending over to tighten the lacesOn my “takkies.”Butterflies cocooned in my insidesAs my head cocked onMy marks.My crouch reversed into a stance andLike a precursor to victoryI recognized you –Round eyeglasses, wide toothy smile.Your eyes beamed through the lensesAs my shuffle gallopedYour arms outstretched inPraise and prideLike a bet won on an unassumingThoroughbred to make first place– I doveInto your embrace.Putting down the trophyQuickly,You lit a cigarette betweenYour fingers, pursed your lips andDrew, gazing out the left eyeWhile I attempted to moveA life sized white knight into theBlack hole space now lacedWith traces of smoke youLeft behind fromyour box of Champions.House = school team names used for student body participation in sports, etc. in South AfricaTakkies = local term for sneakers, trainers, running shoesWanderlust.A hint of adventureRemedies her cooling heart;A lioness watching its preyShe makes no mistakeIn her advanceAnd landsRightWhereSheMusterStill a 1980 American Citizen DreamThank you, America, for teaching meAbout a dream and the extentsThat I will go to achieve itFiner things and fickleTo my heart’s deepest desireTo roam the deserted parts of the globeAway from humdrum in the machineYou gave new meaning to sex and longevityAnd harmonized notions of romance, modern romanceA silk film on screen I wear in the sweltering summer heat of the westAnd inner cities you’ve rearedThe colour of my skin giving me new meaningThe identity I already thought was confusing melted deeperInto the pot of your vague appropriationsFriendships old renewed after decadesLearning progress through due processWithout it you WILL NOT SUCCEEDAn undying gambitA gamble on a dreamBut most of allMy mother who shook her own worldTo make it hereBattling institution and reverse racismSupport by the hour for your dollarScrubs on since 1980That brought her all the way hereAnd still she won’t do itBut maybe one day she willBut begs why you’ve been soHarsh and fang baringTo someone who’s supported your dreamSince before I was bornNew York City Poems

By Tom Pennacchini

A Bay Wolf in the Apartment of Eagles

Come the dawning

Regardless of mood

I like

To take some moments

To

cut

the

Rug

in the morn light of my roomdip

move

vibe and shimmy

I do the spasmodic

To the

RadioAmusing me self

And digging

The reflection of my Moves as

Silhouetted

in the Van Gogh prints

On my wallsOh yeah

I Got It

A Rock’n’roll kid

from

Get to GoneIt’s my

Days

Dawnand

Regardless of mood

This is my private morning

Clarion Call

and my

Free Flying

Fuck It All

Lone FolkieThere is a squat/stout duffer in a windbreaker and a Mets cap on the outskirts of the park

playing a rickety 5 string and hoot ‘in and holler’ in.I have no idea what he is singing.

There is no discernible melody.

Every now and then he stops/ freezes/ puts his forefinger in the air

to take some sort of measure

before plunging back into his flailing guitar.

After another stuttering burst he will stop/

then let loose with an elongated cry to the sky/

punk operatic/ stylenobody seems to stop/and listen/he does not have a container for contributions and probably would not get much trade/

he is playing/for his own/self/and that is / enough

It’s/utterly senseless/ wholly out of key.

Beyond the realm of anything/

resembling cohesive musicality

/rambunctiously obtuseyet imbued with an innocence that casts proficient excellence into a pallid light.

His songs/ performance/ like life/ a messy and inconclusive/ thing/

You can have/ your polished practice and Carnegie aspirations/

and make of that an evening/ with class

but I like the way this codger lets her rip/

this ragged chanteur/

airs it out/ no class/ no talent/ but lotsa / styleShine on

Shine on oh perishing republic of dreams

oh community of outcasts

Art in the essence with no need

for product or commodity

Convivial souls rabid rebels minds afire

Provincetown dunes Christmas Eve

Greenwich Village the 20’s to the 50’s

Innocent fervent glass of beer cafeteria a quarter

Shine on oh perishing republic of dreams!Winged Ones

Bustling old fella dashing biddly bop by dressed to the nines

with briefcase stuffed under his arm equipped with fixed maniacal grin jabbering to himself while confirming his expressions

to an equally jazzed and jaunty westie he calls Ralph trailing exuberantly behind

lets me know

that there are actually still some living beings out there

to learn fromNarcissus Stereo

Whenever I am in a roomful of actors (christ don’t ask) I am buffeted and overwhelmed by waves of nausea

for some truly baffling reason they identify as artists but never discuss art

they do however love to dither on politics and dish presidents oh and

movies natch but Rembrandt or Brueghel nahhhhThey are ostensibly interpreters of script but never discuss literature excepting Shakespeare which they have been dutifully schooled upon

(what the fuck – – art and … school?)shame can be a necessity (we’re people after all)

where’s the sense of it?

Put In Place Out of Place

I have been shut down occasionally vis a vis my mutterances on the street corner and while attempting movement on the frenetic city sidewalks

I like to do it in order to sort of clear a path and in order

to facilitate and free up navigation-

at times I’ll say “I gotta do a little bit a that swivel and swerve” – or as I zig and zag out a maneuver – ” just the slip n slide” whilst moving and weaving thru the throngs

Other times I’ll emit a bit of a shriekOr

Announce constructive critiques regarding their aptitude for city walking like

“Another dolt – doing the diagonal “! – admonishing the herd – “I am begging for mercy “! “Good heavens – cease and disperse the cluster “!

Their compass clearly needing alignment (my god do they drive like this?) –

Must make sure that shit is correct! I am trying to move freely goddamnit!

“I gotta circumnavigate stone agony”! … “Becomes imperative “!!

Perhaps I’ll be clogged by a stroller

“Nightmare in perpetuity “!

A Yammerer on the phone AND a stroller-

“You know they’re out to torture”!!Then there are the odd times in which I need to be schooled –

One time I was loudly griping about a construction obstruction (it is all over and everywhere) and a yob kinda bloke said ” its NY – Stop complaining”…

I readily complied.

Another time I was wading through a crowd announcing, “I know my babies ain’t shy” whereof a charming lass turned to me and demurred “How do you know I’m not shy?”

I fluttered – gurgled some kind of non-sequitur before feathering and loping off.

Well perhaps I’m not a confrontational sort but there you have it

just trying…trying to move along.New York City Poems

By Mary DurocherChelsea Hotel #2

A sparrow perches on the subway platform at 36th Ave. I’m alone and waiting for the W train. I can’t keep track of each fallen sparrow. Leonard Cohen wrote that, not you. Wait, no, it’s, I can’t keep track of each fallen robin. The song is about Janis Joplin. In an interview Cohen said he regretted revealing that Joplin was his muse. Mostly because of the song’s reference to her giving him head on the hotel bed. I think being a dead robin is worse.

The sparrow darts off into November’s bleak sky. I can’t keep track of each fallen sparrow. I watch its silhouette shrink and I remember the crows that circled Mt. Haystack’s peak when we went in June. I was Joplin and you were Cohen. I teased you by loudly labeling the crows as an omen. You stared in awe at their formation. I was always too expressive, with my feather boa and unruly locks. You were always too silent, consumed by your meditations.

I don’t know why I envision this. You and I were not notorious lovers. A piss-scented subway platform is not the peak of a mountain. Riding the W train is not being with you. A sparrow is not a robin. Neither of these birds are Janis Joplin.

Naivety

The seer of the Lower East Sidesways on a corner,crying to New York’selectric eternity.Her mascara dripsand cakes into her skin,black stockings snagged,her party dress swirlsin the rotten breeze.Swarms of men,fresh from their glass houses,pass her unholy pulpit,breath hot and sharptheir taunts burst at her feet.She and I are not similar.I am an adolescent,a blurred outline.She is ablaze and immune,a myth with a chipped tooth.When the visionary sees meshe grabs my hands.Angelic, angelic, angelic.I yank away.I reject her now.I reject her still.Her shadow is following medown Orchard Street.It darts acrosswalls,wounded in fury

at my inability to see.

-

Six Poems – Tobi Alfier

Before the ScatteringWe knew that soon we’d split apartlike the lumber we shattered and carriedup the dunes to our private place,the sound of the ocean just over the ridge,breeze turning to wind with the lowering sunand our thoughts turning inward to remember.This day’s brilliance will become the very historyof light. This evening’s laughter the very historyof probably never again. Fireshadows mottleour faces. And the unseen tide rises and falls.Out come the thick sweaters even with the fire’s heat.We reminisce. We kiss. We dance.The lovers and the never-to-be lovers—all the sameon this last night. Some of us will sleep herespooned close to the embers, the Constellationsof Sadness and Joy whispering to us in the dark.Some of us will be on our way—a train to catchor other reason to avoid the morning glowof tears we all shed in the dark. Supposedly grown,we are like children listening for the ice cream cartof Dreamsicles and next steps. But this night we willalways recall, no matter what happens tomorrow.The End of WinterWe see the back of him as we watch the water.He’s hunched over a splintered picnic tableoddly angled into a slow hill down to the road.He wears the uniform of all retired local fishermen:well-worn denim jacket over hand-knit sweater,black watch cap pulled down over his ears. A ruddy,windblown profile. We see a pencil clutchedin one hand, the other arm holds a notebook downto keep it from gusting to the sea.He writes his observations just as we do,pays no attention to us or anyone else, not evenhis wife hollering for him to bring in wood—but gulls hunting low-slung fiddler crabs, a ferryrounding a far-off point and heading towardthe harbor to disembark city day-timers achingto quiet their minds for just a short minute,stocks of beer for the pubs, full creels and provisionsfor hotel restaurants…that he notes.This beloved island. Where hours slip slow like seabirdsand the shore is mainly quiet. A few collectorsof beach glass, and always the sad silhouetteof one person who knew their embrace was forever—they won’t be returning to the mainlandwith the last ferry, not today, not tomorrow.We see their hurts where a truth is buried in every scar,the silence of their pain like a feather,falling from a wing.OffshoreThe sea tells its story in more than myths and shipwrecks,it is mothers and sons, sons and lovers, lovers and husbandsas well as all things living or dying, or dead—the thick kelp forest hides meteorites from heavenand much sea life, some we can’t even describebecause we have no words for it, all preservedin the salt of witness, stories passed downfrom generations, changed very little as they go.I catch her often on beaches that thread the coast,always gazing seaward, lowering her head to light a smokeeven in damp winds, her collar drawn up against the cold.The day is already etching away in shadows—she has not found what she searches for, only gullscrying up and down the flattened water. They carryno answers. I’m fearful of approaching her to askwhat she seeks. She won’t find it tonight, I’m sure.Flying clouds muscle in on the gulls, change starsinto scraps of constellations. The sky over the seaturns tungsten-gray to blue-black. Late workers on breakcongregate in the beach parking to pass a flask.It’s time for the woman to move on to her next lookout.I don’t know where she’s going or how she’ll get there.May her ghosts find their sea legs and bring her peacebefore the next morning breaks—my unspoken wish for her.Calendar Girl – AprilSpring is a fading map of winter.As the sun strips ice from fields,she exhales. It’s time to put downher hair, put on her bracelets,and spin and spin and spinon the new lawn carpeting upspiky between her toes,and smelling like a world reborn.It’s all about the boots and music,Saturday night dances springing upfrom here to across the border,honky tonks, jukeboxes and radios all night,a wealth of warmth falling on bare shouldersall day. A balmy breeze. A hardblue sky.Sundress stained with the beginnings of flowersand luminous fragments of joy touch everyone.She drinks in the colors, pure and sweet,packs away the winter beiges and grays,digs out her sandals, follows the soundsof water over river stones, the rush of wings.Calendar Girl – MayAunt May settled herself down on a few acresfour hours and lightyears away from her family.She woke each morning through spring’s open windows,fingers twirling through her fine gray hair, listeningfor the music deep inside while looking at the orchardsthat had come to be both savior and friend.Peaches and apricots on her tongue like her husband,blessed be, and her companions—never introducedas anyone’s uncle and fooling no one,they’d last as long as a spare hair on a pillowcasebefore it went into the wash. Aunt May was our real aunt.We knew she’d grown up rough, only guessed the storiesfrom the awkward silences between grown-upsif we marched in for some attention. We never got to hearthe good stuff—surrounded by a thick musk of secretslike lovers in by-the-hour motel rooms. Not one word.We loved Aunt May and she loved us. We huggedher tight when we could. At the end, when the storm brokeand sunlight fell wild over everything in life and in dream,she was our wildflower who opened private and alone.Road TripWe watch a young girl skip down to the water’s edgeas we stroll the shore, warming in the mid-morning sun.Georgia—her parents had taken a road trip cross-countryand that’s where she was born—rubs her 34-week bellyas we talk about names. Our hope’s as full as a harvest moonshining in a small window. Georgia had always wanted April,May, June or July but it’s coming up on August now,and we’d opted for surprise. So much to discussin this privacy with a short shelf life and many loved oneswith opinions. The sweet scent of cut grass rolls over usfrom an upwind field and I kiss her hands. Her summery dressslips down one shoulder in that way it does. Gets me every time.Forget the walk, it’s time for wine. And juice. And the list:no relatives still living, no first loves, second loves, any loves.We go to the harbor, look at names stenciled on hard-workingtrawlers. The light leans into afternoon. Georgia leans into me.She draws her finger across my lifeline as we both see the right choice,the early breeze blesses it as favorable as a soft kiss. -

Mister Brother

Mister Brother is shaving for a date. Mister Brother likes getting ready and he likes having had sex. Everything in between is just business.“Hey, Twohey,” he says. “Better take it easy on the sheets tonight, Mom’s out of bleach.”“Twohey (that’s you if you’re ready to wear the skin for a while) says, “Shut up, you moron.”“Ow,” Mister Brother says, expertly stroking his jaw with Schick steel. Don’t call me a moron, you know how upset it gets me.”Mister Brother, seventeen years old, looks dressed even when he’s naked. His flesh has a serenely unsurprised quality not common in the male nude since the last of the classical Greek sculptors cut his last torso. Mom and Dad, modest people, terrorized people, are always begging Mister Brother to put something on.“Shut up,” you tell. Him. “Just shut up.”You, Twohey, I’m sorry to say, are plump and pink as a birthday cake. You are never naked.“Twohey, m’dear,” Mister Brother says “haven’t you got any pressing business, ahem, elsewhere?”You say, “You bet I do.”And yet you stay where you are, perched on the edge of the bathtub, watching Mister Brother, naked as a gladiator, prepare himself for Saturday night. You can’t seem to imagine being anywhere else.Mister Brother rinses off, inspects his face for specks of stubble. He selects an after-shave from the lineup. To break the scented silence, you offer a wolf whistle.“Mister Brother says, “Honestly, if you don’t let up on me, I’m going to start crying. I’m going to just fall apart, and won’t that make you happy?”Mister Brother is a wicked mimic. When you tease him, he tends to answer in your mother’s voice, but he performs only her hysterical aspect. He omits her undercurrent of bitter, muscular competence.You laugh. For a moment your mother, not you, is the fool of the house. Mister Brother smiles into the mirror. You watch as he plucks a stray eyebrow hair from the bridge of his nose. Later, as the future starts springing its surprises, and you find yourself acquainted with a drag queen or two, you will note that they do not extend to their toilets quite the level of ecstatic care practiced by Mister Brother before the medicine cabinet mirror.“Hey honey, come on now; don’t cry. I didn’t mean it,” you say, in an attempt at your father’s stately and mortified manner. Imitation is not, unfortunately, the area in which your main talents lie, and you sound more like Daffy Duck than you do like a rueful middle-aged tax attorney. You try to hold the moment by laughing. You do not mean your laughter to sound high-pitched or whinnying.Mister Brother plucks another hair, rapt as a neurosurgeon. He says, “Twohey, man.” He says nothing more. You understand. Work on that laugh, okay?Where are you going?” you ask, hoping to be loved for your selfless interest in the lives of others.“O-U-T” he says. “Into the night. Don’t wait up.”“You going out with Sandy?”“I am, in fact.”“Sandy’s a skank.”Mister Brother preens, undeterred. “And, what’ve you got lined up for tonight, buddy?” he says. “A little Bonanza, a little self-abuse?“Shut up,” you say. He is, as usual, dead right, and you’re starting to panic. How is it possible that the phrase, “lonely, plump and petulant” could apply to you? There is another you, lean and knowing, desired, and he’s right here, under your skin. All you need is a little help getting him out into the world.“So, Twohey,” Mister Brother says. “How would you feel about shedding your light someplace else for a while? A man needs his privacy, dig?”“Sayonara,” you say, but you can’t quite make yourself leave the bathroom. Here, right here, in this small chamber of tile and mirror, with three swan decals floating serenely over the bathtub, is all you hope to know about love and ardor, the whole machinery of the future. Everything else is just your house.“Twohey, brave little chap, I’m serious, capish? Run along, now. On to further adventures.”You nod, and remain. Mister Brother has created a wad of shifting muscles between his shoulder blades. The ropes of his triceps are big enough to throw shadows onto his skin.You decide to deliver a line devised some time ago, and held in reserve. You say, “Why do you bother with Sandy? Why don’t you just date yourself? You know you’ll put out, and you can save the price of a movie.”Mister Brother looks at your reflected face in the mirror. He says, “Out faggot.” Now he is imitating no one but himself.You would prefer to be unaffected by such a cheap shot. It would help if it wasn’t true. Given that it is true, you would prefer to have something more in the way of a haughty, crushing response. You would prefer not to be standing here, fat in the fluorescent light, with hippopotamus tears suddenly streaming down your face.“Christ,” Mister Brother says. “Will you just fucking get out of here? Please?”You will. In another moment, you will. But, even now, impaled as you are, you can’t quite remove yourself from the presence of your brother’s stern and certain beauty.What can the world possibly do but ruin him? Mister Brother, at seventeen, can have anything he wants, and sees nothing extraordinary about that fact. So, what can the world do but marry him (to Carla, not Sandy), find him a job, arrange constellations over his head just the way he likes them and then slowly start shutting down the power? It’s one of the oldest stories. There’s the beautiful wife who refuses, obdurately, mysteriously, to be as happy as she’d like to be. There’s the baby, then another, then (oops, hey, she must be putting pinholes in my condoms) a third. There’s the corporate job (money’s no joke anymore, not with three kids at home) where charm counts for less and less and where Ossie Ringwald, who played cornet in the high school band, joins the firm three years after Mister Brother does and takes less than two years to become his boss.All that is waiting, and you and Mister Brother probably know it, somehow, here on this spring night in Pasadena, where the scents of honeysuckle and chaparral are extinguished by Mister Brother’s Aramis and Right Guard, and where the souped-up cars of Mister Brother’s friends and rivals leave rubber behind on the street. Why else would you love and despise each other so ardently, you who have nothing but blood in common? Looking at that present from this present, it seems possible that you both sense somewhere, beneath the level of language, that some thirty years later he, full of Scotch, pecked bloody from his flock of sorrows, will suffer a spasm of tears and then fall asleep on your sofa with his head on your lap.That night is now. Here you are, forty-five years old, showing Mister Brother around the new hilltop house you’ve bought. As Mister Brother walks the premises, Scotch in hand, appreciating this detail or that, you feel suddenly embarrassed by the house. It’s too grand. No, it’s grand in the wrong way. It’s cheesy, Gatsbyesque. The sofa is so . . . faggot Baroque. How had you failed to notice? What made you choose white suede? It had seemed like a brave, reckless disregard of the threat of stains. At his moment, though, it seems possible––it does not seem impossible––that men don’t stay around because they can’t imagine sitting with you, night after night, on a sofa like this. Maybe that’s why you’re still alone.Tonight you sit on the sofa with Mister Brother, who lays his head in your lap. You tell him lots of people go through bad spells in their marriages. You tell him things at work will turn around after the election. Although you still call him by that name, this man is not, strictly speaking, Mister Brother at all. This is a forty-eight-year-old nattily dressed semi-bald guy with a chain around his neck. This is a tax attorney. Here he is and here you are, speaking softly and consolingly as the more powerful constellations begin to show themselves outside your sliding glass doors.And here you are at fourteen, in this suburban bathroom. You stand another moment with Mister Brother, livid, ashamed, sniveling, and then you finally force yourself to perform the singular act that should, all along, have been so simple. You leave him alone.“So long, asshole,” you say weepily as you exit. “And, fuck you too.”If he thought more of you, he’d lash out. He wouldn’t continue plucking his eyebrows in the mirror.You go and lie on your bed, running your fingers over the stylish houndstooth blanket you insisted on; worried, as always, about the stains it covers. You hear Mister Brother downstairs flirting with Mom, shadowboxing with Dad. You hear his Mustang fire up in the driveway. You lie on your bed in the room that will become a guest room, a junk room, a home office, and then the bedroom of a stranger’s child. You plan to lose weight and get handsome. You plan to earn in the high five figures before you turn forty. You plan to be somebody other people need to know. These plans will largely, astonishingly, come true.As Mister Brother roars away, radio blasting, you plan a future in which he respects and admires you. You plan to see him humbled, weeping, penitent. You plan to look pityingly down at him from your own pinnacle of strength and love. These plans will not come true. When the time arrives, reparations will be negotiated between a handsome, lonely man and a much older-looking guy in Dockers and a Bill Blass jacket; an exhausted family man who’s had a few too many Scotches. Mister Brother won’t come at all. Mister Brother is too fast. Mister Brother is too cool. Mister Brother is off to further adventures, and in his place he’s sent a husband and father for you to hold as the city sparkles beyond the blue brightness of your pool and cars pass by on the street below, leaving snatches of music behind.“Copyright@1998 by Michael Cunningham. Originally published in DoubleTake Magazine, Fall 1998. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission of Brandt and Hochman, Literary Agents, Inc.

-

Poetry Potpourri

Three PoemsBy Timothy ResauRendezvous at St. Paul’sRendezvous outside St Paul’s stained-glass windows—lips locked—breathing crowdedwith floating radiation—Why say more whenJesus is behind the wall,selling knives to Lord Byron,as Ms. Lamb squintsblue eyes at a rag-muffin hillbillyriding a pony down the asphalt hill?A real woman in these lost-n-found arms.And in the backyardAmerica’s cooking its dreams:plastic poets dreamingin bowling alleys—neighbors sellinglies painted Catholic.The radio plays broken Mozart,& babies are found in junkyards—An aroma of gasoline driftsthru the air—& acne is real!A tattoo of loveis on her face forever—The kiss of life fromthe high poet, selling paperbackbooks for a fin—Glitter & goldsummer & cold—yes, I’ll be old!Acid LoveBroken love ride—love wreck-wired—the outcomes always the same—unreality-a cold chill – iced!The anguished heartthrobbing, throbbing,pumping, purplecold fear — alone.The design itself — wrecked.A high of love — lost.Love constellation—stellar vibrations—a child’s pleading eyes—A young black man on corner,waxing mustache, saying:I’ll never come down from this—like a bird frozen in eternal flight.Everyone’s a delusion,trying to be real—The experience is all….Nobody Thinks I’m HumanThe full moon hid across my face—my shadow missing in the pale light,& they kept saying that they wouldn’thave missed it for the world.Things you never forget—like the murder of love.The pain of each death–the fearthe hatethe waiting.

Three PoemsBy Timothy ResauRendezvous at St. Paul’sRendezvous outside St Paul’s stained-glass windows—lips locked—breathing crowdedwith floating radiation—Why say more whenJesus is behind the wall,selling knives to Lord Byron,as Ms. Lamb squintsblue eyes at a rag-muffin hillbillyriding a pony down the asphalt hill?A real woman in these lost-n-found arms.And in the backyardAmerica’s cooking its dreams:plastic poets dreamingin bowling alleys—neighbors sellinglies painted Catholic.The radio plays broken Mozart,& babies are found in junkyards—An aroma of gasoline driftsthru the air—& acne is real!A tattoo of loveis on her face forever—The kiss of life fromthe high poet, selling paperbackbooks for a fin—Glitter & goldsummer & cold—yes, I’ll be old!Acid LoveBroken love ride—love wreck-wired—the outcomes always the same—unreality-a cold chill – iced!The anguished heartthrobbing, throbbing,pumping, purplecold fear — alone.The design itself — wrecked.A high of love — lost.Love constellation—stellar vibrations—a child’s pleading eyes—A young black man on corner,waxing mustache, saying:I’ll never come down from this—like a bird frozen in eternal flight.Everyone’s a delusion,trying to be real—The experience is all….Nobody Thinks I’m HumanThe full moon hid across my face—my shadow missing in the pale light,& they kept saying that they wouldn’thave missed it for the world.Things you never forget—like the murder of love.The pain of each death–the fearthe hatethe waiting.Two Poems

By Scott RenzoniRed Hair, Blue Jacket

The blue of her jacket was primary.You wouldn’t’ve called itanything other than blue.Not cerulean or indigo or delft,and with no modifierslike baby or powder, sky or navy.That hair, though!Cascading over the collar…An autumn sunset over Walden Pond.The embers of humanity’s first fire.The way the sky sometimes looksat dawn when you wake upnext to a new lover.I’m sure she doesn’t think of it that wayin the mornings, before coffee,as she drags her combthrough fireand runs her fingersthrough flame.A Refrigerator in PatersonHis wife must have been beside herself.Not one plum left for breakfast,and that maddeningly casual note:“this is just to say”,despite having been told, probably repeatedly,they were intended for the morning table.And that report about how sweetand how cold they were—insult to injury, making the“forgive me”as hollow as the bowl with its gnawed pits.Perhaps there had been other notes,making excuses for whythe dog wasn’t walked,the garbage not removed,the car not washed,or the Sunday paper left on the stepto soak through in an afternoon rain.Or perhaps it was the only one,scratched on a scrapin the middle of the night,knowing that no noteand no apology could ever fully explainhow sometimes even plumsare too beautiful to be left alone. -

Six Poems – Jared Beloff

Firstborn of the Dead

after Pablo Neruda’s “United Fruit Company”The sky vanished like a scrollrolling itself up, and every mountainand island was removed from its place – Revelation, 6:14When the sky vanished, it wasall foreseen on the earth, parceled out,maps marked in oil: ExxonMobil, GazpromBritish Petroleum, pipelines carving latitude,dominion over the earth.Along shifting coastlines, flies helixed over shipsforging new routes, past islands of dying treessubmerged dunes, silt ruddy with blood and bleached corallike treasure or a burial of tombs, homes sinking like rotten teethon the floodplain: a woman walks within boarded houses,seven Xs across seven sealed doors,the river’s flood thrashing beyond the levies.Meanwhile, an eye of fire ruptured in the Gulfa wall of flame replacing the sky in the West:meanwhile, the Fruit Companies sprayed suntan lotionon withered fruit, leaned on their worn bodies, first generationspicking cherries in the dark, children cutting melons in the dark,their restless bodies rooted to the fields like windswept stalks—and lo, they brought greatness and freedom and comfortfor the lowest prices packaged in plastic and cellophane,their juices glimmering under the skin in the market’s fluorescent light.The Ship of TheseusThe ship they held in harborbecame a relic, a memorialfor honor or battle, remembereda man whose name tremblesat the tooth’s edge, trying to holda sound they could not keep:Each rotten board a treeeach tree a root returning.What is recognizableis never certain: the waya leaf breathes in lightor a wave will curl its undoingback against the boards.Each root a tendril tunnelingto find its proper ground.Our taste buds change,every seven years they shedold favorites, find joy in new flavor:tang of blood, sweat’s brineraising new questions:How do we forgive the timetaken to forget ourselves?A forest burns across continents,a glacier calves cities of icewhich only just rememberthey were once the ocean.How long do we havebefore we forget what wehave replaced: each nailand tooth, the splinter’s weeping?Watching Time Lapse Videos with My DaughterThe world pirouettes on a screenseveral suns leap over a shadowed citycirrus clouds meet then scatter across stage,a moon waggles in the wings. We don’t blink,pupils widening like sinkholes.At this speed we are tail light thin,reduced to ribbons and flares along the freeway,raw scars of flame, a curtain of smoke swellingto cover the wind’s tapestry, pinions folded over loose threads,replacing the sky.Her curiosity breaks our momentum:When will we die? In our hands a forest glows,the heave of Queen Anne’s lace, a stand of sunflowersstem their way through soil, stretch to their zenith,turn their heads down as if to watch, as if to pray,looking back over the earth they had left,unable to remember the cause of their leaving.Tomorrow is Neverafter Kay Sage, 1955There is no skyonly the haze we drape over ourselves.We swell in our scaffolding, towersreflecting each pleated thought.There is no tideonly oil pluming across water.we slick and dissipate, driftingin the sun’s overzealous spin.There is no earthonly soot and the animals retreating; a doelays back down into the press of summer strawwary of the ark we never built.Don’t look backfor the dappled green, the startled bloomof spring, hooked as we are—Tomorrow is never.Revolutionreset the gene that lies dormant,let your hand retract, reach away.crawl with withered legs, belly grippingback over the mess of leaves,and trailing bodies to what we once were:remember this sound? the spinning world,blood’s hammer and drum, the ocean’s wash,a withdrawal in your ear—turn back,feel the slither and fin, shaking, resurgent.let it rise up, teeming, primordial:your lips curling around the callnaming what’s undiscoveredEkphrasisI will not describe the grapeswhich are not grapesnor the fish whose chest is cut openwhich is my father.I will not play with color nor light,nor the arrangement of objectswhich are harsher, more cleanthan the sky outside.I will not draw upon shadowsnor trace each drooping petalnor find meaning in a paring knifewhich wobbles like a brush stroke.Do not approach the windowthat wrings itself in reflectionagainst empty wine bottles.There is no view, only your looking. -

Mona Lisa’s Third Eye: Twenty-five Haiku

talk is cheap

but even at that

the dinosaurs have no cash

*

in Coco Chanel’s apartment

a giant meteor

and a puff of smoke

*

drifting toward sleep —

dark perfume

falling off a cliff

*

he rises

at night to write down

strange chords

*

even before

he could walk, his crib

floated on water

*

diamond —

a gathering

of windows

*

falling rain

reveals the mirrors

hid in clouds

*

a treatment

for claustrophobia — to swallow

elixir of mirrors

*

toward my back door

slow as a glacier

a graveyard flows

*

a tiny uncharted island —

a place

to hide from Egypt

*

mummy cloth

in a few centuries

I’ll unwrap myself

*

to prepare

for the Sack of Rome —

tea and toast

*

guns grow limp

unable to get hard

they die out

*

changing tastes –

once-famous paintings

are melting

*

behind Mona Lisa’s

third eye a temple of glass

still under construction

*

wet or dry

the stones are happy

to be a cathedral

*

inside a marble head

there is no memory

of Ancient Rome

*

in Kansas City

in a house of glass

a banker consults an astrologer

*

reaching up

Gertrude Stein catches

a bird in any sky

*

Gertrude Stein is laughing

a ball is falling to pieces

who fly away

*

just when I almost

saw the wind’s face

it changed

*

in Antarctica

researchers hallucinate

in fields of snow

*

like the Great Pyramid

there are many snowflakes

I’ll never see falling

*

in Gertrude Stein

patterns emerge

as fish in flight

*

it’s too beautiful –

I cannot finish

the novel